Yemen: This is about geopolitical, not sectarian, interests Politics

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Wednesday, April 1, 2015 12:28 - 2 Comments

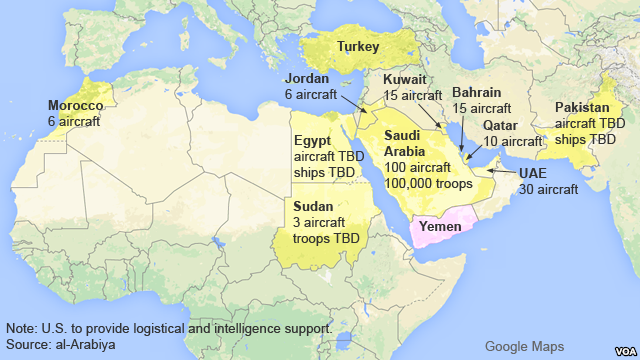

Countries taking part in the Saudi-Led military intervention in Yemen.

On Wednesday 25th March, Saudi Arabia’s Defence Minister, Mohammad bin Salman, oversaw airstrikes against the Shia Houthi rebels in Yemen. His decision was backed by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), as well as Pakistan, Jordan, Egypt, Sudan, Turkey and Morocco. This is not the first time Saudi Arabia has intervened militarily in the affairs of a neighbouring state. A similar strategy was implemented in 2011, when Saudi troops were deployed in Bahrain to quell growing civilian strife at the peak of the ‘Arab Spring’.

For many observers, the Saudi-led campaign against the Houthis is the latest episode in an ongoing wider cold war between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Yemen, many argue, is the latest battleground front – joining Lebanon, Bahrain, Syria and Iraq – where the region’s chief power-brokers have been locked in a proxy war for the best part of 20 years.

The media coverage over the past week has painted the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) intervention in Yemen along predominantly religious lines, referring to the anti-Houthi coalition members as a collective group of “Sunni Arab states”. However, whilst the “Sunni Arab states” label is factually correct in isolation, the current conflict pitting the Houthis against President Abd-Rabu Mansur Hadi’s loyalists as well as Al Qaeda elements is more than just a sectarian conflict. In most military conflicts, there is a wider socio-economic, geopolitical and religious context, and Yemen is no exception.

The sectarian narrative

The Sunni-Shia divide was the first schism in Islam, dating back over a thousand years. It was a political split over succession that later became a theological divide manifesting itself militarily throughout the centuries since; including during the Crusades, the rise and fall of the Ismaili Fatimid dynasty, and numerous wars between the Ottoman Caliphate and the Persian Safavid Empire.

The twentieth century saw a re-emergence of the Sunni-Shia discord. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran immediately became a political and religious adversary of Saudi Arabia. With the exception of Iran – and Iraq after the first Gulf War – the majority of Gulf States are both predominantly Sunni and host US military bases. Indeed, Iraq and Bahrain are the two countries where Shias make up the majority of the population, with significant Shia communities in Yemen, Kuwait, Lebanon and Turkey.

Iran, with its self-sufficiency ambitions and nuclear programme, has presented itself as the biggest obstacle to Western dominance in the region. Along with the Assad regime of Syria, and the Lebanese militia group Hezbollah, this alliance has called itself the ‘Axis of Resistance’ – a riposte to George W Bush’s infamous “Axis of Evil”. With post-war Iraq under a Shia-dominated government, and the rise of Yemen’s Houthis, the regional balance of power has shifted further in Iran’s favour.

The Sunni-Shia divide is steadily becoming the defining narrative of current conflicts in the Middle East; from the Syrian civil war which has spilled into political instability in Lebanon, to the ongoing chaos in Iraq, and now the proxy war in Yemen. However, one must wonder whether this sectarian paradigm, unquestioningly peddled by the mainstream media, is an accurate one, and whether the intervention in Yemen really is about safeguarding the country’s Sunnis from the Houthis, especially when Saudi concern for the besieged Sunnis of Syria, Iraq and Gaza had remained resolutely rhetorical in nature.

Some have suggested that Iran harbours sectarian aspirations to revive a neo-Safavid empire stretching from the Levant to Khorosan. With a self-professed ‘Caliphate’ wreaking havoc in Iraq and Syria, and a Turkish Premier who’s been described as an “Ottoman Sultan”, the religious dimension of regional geopolitical dynamics cannot be dismissed lightly.

Iran and Saudi Arabia’s cold war

Saudi Arabia

Over the past century, the oil-rich kingdoms of the Gulf have faced a number of ideological threats: Arab Socialism during the Cold War, political Islam in its many forms – from the Muslim Brotherhood to Al Qaeda – and ‘revolutionary Iran’ since 1979. The GCC nations, led by Saudi Arabia, have adopted different strategies in dealing with these threats, though usually implementing policies that meet with tacit or explicit US approval.

Last Wednesday, the US Secretary of State, John Kerry, held a conference call with Gulf ministers to discuss the Yemen crisis. According to a State Department official, Kerry “commended the work of the coalition taking military action against the Houthis”, and noted Washington’s support “including intelligence sharing, targeting assistance, and advisory and logistical support for strikes against Houthi targets.” The official added: “The ministers all expressed their support for political negotiations as the best way to resolve the crisis, but also noted that it is the Houthis who have instead waged a military campaign.”

Many see these latest developments as an attempt by Saudi Arabia’s new ruler, King Salman, to reorganise the political order in the region. Salman has been vocal about his desire to repair old relationships that had been damaged during his predecessor’s reign. The improvement in relations with Turkey, Qatar and even the Muslim Brotherhood is a testimony to this new approach. Establishing a de facto military alliance with Pakistan, Morocco, Sudan, amongst other ‘Sunni states’ to counter Iran, is further evidence of this revised geopolitical strategy.

The formation of this ‘Sunni bloc’, consisting of nations with strong military capabilities, could represent a historic turning point for the Arab world, particularly its approach to internal conflicts. Yemen is a particularly complicated case, long seen as a thorn in its side by Saudi Arabia. Effectively a failed state, Yemen has been plagued with tribal, sectarian and political strife for decades, as well as a significant Al Qaeda presence.

In this context, Saudi Arabia’s political and military track-record in Yemen has been far from successful. Furthermore, in the absence of a functioning Yemeni army, state infrastructure and institutions, it is likely that the Saudi-led campaign will last longer than initially planned. As swathes of the country falls under Houthi control, Saudi Arabia is adamant it will do all it can to protect its borders. Meanwhile, Al Qaeda is seen as an equally serious threat, flourishing in the power vacuum created by civil war and foreign intervention. Indeed, Saudi Arabia is anxious to prevent Yemen’s Sunnis from flocking to Al Qaeda in response to Houthi advances, a key factor behind the intervention that has been largely absent from mainstream coverage and analyses.

Iran

For many observers, Iran has been as its most effective in achieving regional prominence through its presence in the region’s failed states. This was evident in Lebanon with the rise of Hezbollah, its unequivocal support for the Assad regime, as well as the US-backed government in Baghdad, and now the Houthis of Yemen. By sending weapons, mercenaries and its elite Revolutionary Guards to fight the Syrian rebels and ISIS in Iraq, Iran has justified its actions under the guise of combating both terrorism and Western imperialism.

Today, US-Iranian relations can arguably be said to be at their strongest for years, with both nations currently fighting ISIS in Syria and Iraq. While the US trains the Iraqi army, Iran trains the Shia militias. Further, for the past four years, Iran has defended Bashar al-Assad by sending Revolutionary Guards to fight the Syrian rebels alongside Hezbollah. It is no secret that Iran implemented a similar strategy in Yemen by arming the Houthis.

Another key factor is the role of oil. Saudi Arabia is trembling at the prospect of the Houthis taking control of Bab-el-Mandeb, the world’s busiest oil thoroughfare. Given that the Strait of Hormuz is currently policed by Iran, such a prospect could potentially present a nightmare scenario for Saudi Arabia and other GCC states. With the likelihood of a deal being reached on Iran’s nuclear enrichment programme, and the possibility of Western sanctions being lifted, the GCC fear the emergence of an economically stronger and assertive Iran. With its considerable oil and gas wealth, Iran would be a major competitor to the GCC, making the current conflict in Yemen – sectarian rhetoric notwithstanding – a game of high economic and geostrategic stakes.

Taking sides?

Many Muslims, both in the West and across the Arab world, have shown support for the Saudi-led campaign in Yemen. For many observers, however, the unfortunate reality is that the anti-Houthi coalition’s display of military prowess is unlikely to go beyond the remit approved by Washington. Needless to say, the region’s populations should have little to celebrate about a war likely to entrench sectarian tensions in the service of the divide-and-rule interests of outsiders.

For many of their citizens, most of the region’s rulers are solely concerned with protecting their Sykes-Picot-delineated fiefdoms. Similarly, there is a growing perception across the region that Iran’s claim to being an adversary of Western imperialism is as farcical as Saudi Arabia’s pretence to be the sole protector of Sunni Islam.

The current onslaught against the Houthis has less to do with sectarianism and more to do with the competition for geopolitical supremacy between two regional powers, as well as the US’s pursuit of continuing hegemony in the Arab world. As has often been the case in the Middle East, there is no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ sides in this conflict, only ugly ones.

2 Comments

Politics | Yemen: This is about geopolitical, not sectarian, interests | aqeelthoughts

Muji Rahman

i think part of the reason why the Arab spring happened was the world witnessing the reemergence of the Asian economies particularly China. This would have at least spurred them on as they want to see the same level of progress. Chances are the more the Asian economies develop the more confident Muslims will become in calling for the resumption of the Khilafah.

[…] via Politics | Yemen: This is about geopolitical, not sectarian, interests. […]