As countries around the world push for nuclear disarmament, the UK and its allies resist Special Report

New in Ceasefire, Special Reports - Posted on Tuesday, January 26, 2021 13:19 - 0 Comments

By Steve Shaw

On Friday, 22 January, the UN’s Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came into force. It is the world’s first legally binding agreement aimed at ending the spread of nuclear weapons. The 52 signatories have committed to stop developing, testing, stockpiling and using nuclear weapons, and the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, said the treaty shows the world wants “tangible action on disarmament”. Dr Rebecca Johnson, the first president of the Geneva-based International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) declared:

“This treaty is the culmination of 75 years of humanitarian activism, from the ‘Hibakusha’ and indigenous survivors of nuclear weapons and testing, to the Aldermaston marchers and Greenham Common Peace Women who helped to ban nuclear testing and get cruise missiles banned and off the roads. Together we’ve persuaded UN governments to bring this ground-breaking nuclear disarmament treaty into international humanitarian law. Our task now is to bring all the nuclear armed and dependent countries into working with the non-nuclear majority to eliminate existing arsenals and universalise, implement and verify the Nuclear Ban Treaty.”

That final sentence refers to the fact no nuclear-armed nation has expressed support for the treaty. Indeed, countries such as the UK and US have gone as far as to ask signatories to withdraw from it ahead of its ratification last week. A letter sent to the treaty signatories was obtained by the Associated Press in which the five original nuclear powers — the US, Russia, China, Britain and France — declare they “stand unified in our opposition to the potential repercussions” of the treaty. The letter continues: “Although we recognize your sovereign right to ratify or accede to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, we believe that you have made a strategic error and should withdraw your instrument of ratification or accession.”

The letter further claimed the new treaty would “turn back the clock” on the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, signed in 1968 to prevent the spread of nuclear arms beyond those five original countries.

Britain has been a vocal opponent of the treaty for years. In 2017, the UK Foreign Office published a strongly worded statement saying the British Government did not intend to sign, ratify or become party to the treaty and that it “will therefore not be binding on the UK”. The Government reasoned that it would not offer support due to “the unpredictable international security environment” that “demands the maintenance of our nuclear deterrent for the foreseeable future”.

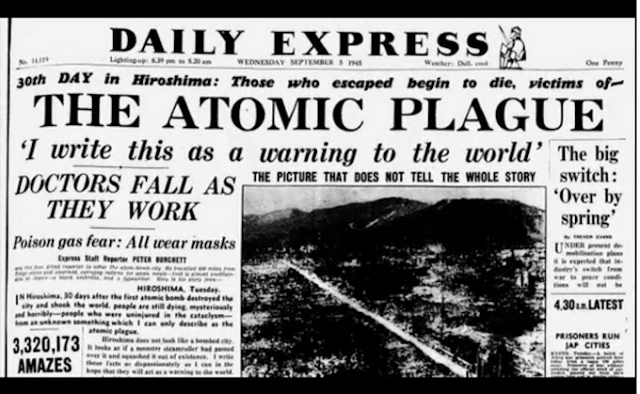

A Warning to the World

The issue of nuclear weapons has become highly politicised in the UK. During the 2019 general election, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was attacked by his rivals for being “not fit to be prime minister” and a “danger” to the country because of his refusal to say he would authorise a nuclear strike. Right-wing newspapers led the criticism, expressing outrage that a potential leader could be unwilling to “press the button”. The Times routinely slammed the former Labour Party leader for his reluctance, with one article centring on security officials criticising the Corbyn for making the UK “less safe”.

This is in stark contrast to the reaction the paper had in August 1945, after the US had dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On 10 August 1945, a piece in The Times read:

“The most ghastly aspect of modern warfare is the widespread slaughter of non-combatants, especially children. The allies have hitherto done their best to avoid it. They may have been unsuccessful but at least they have tried. Here however there is no pretence… And by whom? By the same allies who barely a year ago were seething with righteous indignation at the indiscriminate brutality of the flying bomb.”

The recent political posturing and media outrage in Britain shows a shocking ignorance of the devastating reality of nuclear weapons and what their actual use would mean. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, Wilfred Burchett was one of the few journalists to travel into the devastated city. Under the heading “I write this as a warning to the world”, he wrote in the London Daily Express on 5 September 1945 that the city did not look like it had been bombed but as though “a monster steamroller had passed over it and squashed it out of existence”.

“Hundreds upon hundreds of the dead were so badly burned in the terrific heat generated by the bomb that it was not even possible to tell whether they were men or women, old or young,” his report continued. “Of thousands of others, nearer the centre of the explosion, there was no trace. They vanished. The theory in Hiroshima is that the atomic heat was so great that they burned instantly to ashes – except that there were no ashes.”

Those who were not incinerated in the initial blast faced the horrors of the bomb’s after-effects. Burchett described slow and painful deaths involving bleeding gums, ears and noses, vomiting blood, hair loss and rotting flesh. “Many people had suffered only a slight cut from a falling splinter of brick or steel. They should have recovered quickly. But they did not. They developed an acute sickness. Their gums began to bleed. And then they vomited blood. And finally, they died,” wrote Burchett.

In total, more than 140,000 civilians were killed in Hiroshima. Days later, the US dropped a second bomb on Nagasaki, extinguishing up to another 100,000 lives. Just one of the nuclear bombs that make up the UK’s Trident Nuclear Weapons System is capable of eight times that destruction and each missile in the UK’s arsenal hold five of these bombs.

British politicians today face condemnation by their political rivals and the British media not for their willingness to carry out possibly one of the biggest acts of mass murder and genocide in history, but for refusing to do so. Indeed, even the British public was left furious over Corbyn’s refusal to commit to using nuclear arms. When his political rival, Conservative leader Theresa May was asked whether she was “personally prepared to authorise a nuclear strike that could kill 100,000 innocent men, women and children,” she simply answered “yes”. A subsequent YouGov poll found that 66% of the British public backed her stance over Corbyn’s, while 60% said they would also support Britain using nuclear weapons.

In one election TV debate, Corbyn said he “would do everything I can to ensure that any threat is actually dealt with earlier on by negotiations and talks”, adding that the idea of using nuclear weapons is “appalling and terrible”.

In one election TV debate, Corbyn said he “would do everything I can to ensure that any threat is actually dealt with earlier on by negotiations and talks”, adding that the idea of using nuclear weapons is “appalling and terrible”.

He implored the audience to understand that if a prime minister was to use nuclear weapons “millions are going to die”. The response from one audience member was to lampoon the potential leader’s stance, “ooh, we’d better start talking!”. Another added that using nuclear weapons was “for our safety”.

However, as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) has pointed out, the British Government’s ongoing commitment to nuclear arms actually puts the country in greater danger, and is contributing to its failure to address current threats, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. For years, a recent CND report notes, pandemics have been designated ‘tier one’ threats to Britain’s security, while nuclear threats are regarded as ‘tier two’. In spite of this, “the governments that produced those risk assessments chose to automatically pour money into a new nuclear weapons system to ‘meet’ this lower level threat, leaving the health system chronically underfunded”.

“Many supporters of Trident claim that nuclear weapons keep the peace by acting as a ‘deterrent’,” the report adds. “This is the false belief that we will dissuade an ‘enemy’ from attacking if they know that we could retaliate with nuclear weapons”.

“During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union may have avoided a direct war – and whether or not that was anything to do with nuclear weapons possession is unknowable – but that didn’t prevent their involvement in wars in Vietnam, Korea, Afghanistan and elsewhere. The nuclear powers have been involved in hundreds of wars since the atomic bomb was first invented in 1945. Having nuclear weapons did not defend France from terrorist attacks, or the US from 9/11 or the UK from the July 7th bombings.

In fact, replacing Trident might encourage more countries to get nuclear weapons and so increase the danger of nuclear war. If countries like the UK and others insist that they need these weapons for their security, other countries will come to the same conclusion. Unstable or isolated states are more likely to seek nuclear weapons in this context”.

Members of the public also give little concern to the massive cost of keeping the UK’s nuclear arsenal. The current Trident missiles are believed to cost taxpayers more than £2 billion every year but a programme aimed at replacing the missiles is expected to cost up to £205 billion.

“The ground is moving under the UK’s feet,” Ben Donaldson, from United Nations Association UK, declared in November, when Honduras became the 50th country to ratify the UN treaty, paving the way for its coming into force this week. Donaldson continued:

“We now have this significant new UN treaty which will sit alongside the other major global treaty on nuclear weapons, the Non-Proliferation Treaty, and drive forward the international community’s shared vision of a world free of nuclear weapons. Governments, international organisations and civil society are sending a clear message to nuclear-armed states that they have lived in fear of fallout for far too long, and want tangible action on disarmament now.”

Leave a Reply