Screening Žižek : on the decaffeination of provocative ideas Ideas

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Monday, March 12, 2012 20:08 - 1 Comment

By Paul Taylor

Introduction

The following contains opinions some viewers may find challenging. (Channel 4 continuity announcer)

The above statement comes from the introduction to the punningly entitled UK Channel 4 programme 4Thought. Apparently un-ironic, this announcement is intoned in the same way as the more usual warning that “The following may contain scenes of a sexual or violent nature that some viewers may find offensive”. For a neophile media, it appears that “challenging” is the new “offensive”. In contrast to the programme’s misleadingly cerebral title, 4Thought‘s true significance actually stems from what it highlights about the media’s disturbingly conservative attitude towards concept-driven discourse, its pre-emptive, Minority Report-like, screening of imminent, incoming ideas.

In such an atmosphere, Kenneth Clarke, the UK Coalition Government’s Justice Minister was lambasted for even attempting to draw a distinction between violent rape and those incidents technically defined by the law as rape (as in the case of consensual sex between teenagers one of whom is a single day under the legal age of consent). Likewise, the Labour Party Shadow Minister, Diane Abbott, was recently pilloried in the media for commenting via Twitter that white people like to play divide and rule with the black community. Although Clarke and Abbott are figures on opposite sides of the political spectrum talking about disparate issues, both were victims of the media’s standard operating procedure – the claustrophobic manner in which the most rudimentary space from which to critically analyse a situation is closed down.

Part of Diane Abbott’s initial defence of her comments rested upon the fact they were taken out of context and that Twitter’s 140 character limit does not allow adequate explanation. Whilst this may be true (and something you’d hope even a vaguely intelligent person would realise before they picked up their mobile phone), this excuse serves to divert attention away from the much more essential structural limitations subsequently imposed upon Ms Abbott by the mainstream media – the systematically predictable and co-ordinated nature of its expressions of indignation. This undermined Abbott’s ability to reason with the public even more than the basic limitations of Twitter.

If each medium remains true to its innermost technical predisposition (e.g. it is difficult to see how TV can escape an ultimate bias for images over words) there are basic limits imposed upon the media’s ability to communicate conceptually yet alone critically. Important and interesting as these technical limitations are, the argument of these three articles focuses instead on a related but different notion of screening. They address the screening of critical thought that occurs in the non-technical, non-projecting sense of the word. It looks at how thought is decaffeinated as a direct consequence of dominant cultural attitudes (albeit pathologically influenced by the pervasively invasive reach of media-sponsored values).

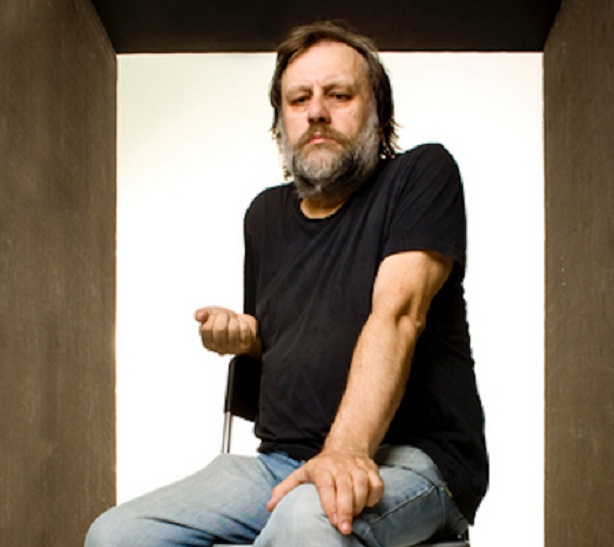

To explore this cultural aspect, I refer to the emblematically media-friendly celebrity intellectual, Slavoj Zizek. With his unique mix of accessible cultural references and esoteric philosophical sources, he enthusiastically engages with the mainstream media more than any other contemporary thinker of equal intellectual stature. (There are many online sources from which readers can witness Zizek in action – a recent favourite of mine is this appearance on the Australian debate programme Q and A.) Most importantly for the issues examined here, Zizek’s willingness to perform under the spotlight helps to expose the way in which conceptual barriers exist not only because of the media’s standard operating procedures, but also because we only pretend to pretend to believe that intellectuals are slumming it when they engage with the media – in practice, as audiences that either expect or mutely tolerate the deracination of knowledge, we all frequently contribute to thought’s profound screening.

To illustrate the case, I draw specifically upon the example of a public talk I conducted with Zizek at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London on May 4th 2011, entitled Screening Thought. Having authored Zizek and the Media, I jumped at the chance to interview him about the nature of the media’s relationship to serious thought but although the evening turned out less successfully than I had hoped, or rather, precisely because things did not quite go to plan, in the spirit with which Zizek likes to cite Samuel Beckett’s rallying call of “Try again. Fail again. Fail Better”, I use the ICA interview as a springboard from which to explore the more general and on-going barriers to serious thought.

Try again. Fail again. Fail Better – The Screening of Screening Thought

There are many great authors of the past who have survived centuries of oblivion and neglect, but it is still an open question whether they will be able to survive an entertaining version of what they have to say. (Hannah Arendt 1954)

Pace Arendt, it is an open question with regard to Zizek as to whether the substance of his message can survive its undeniably entertaining mode of delivery. In Zizek and the Media I explore how Zizek’s idiosyncratic theoretical approach helps us better understand the media’s misleadingly naturalized forms of ideology – its seamless production of what Roland Barthes refers to as that which “goes without saying”. In Zizek’s own case, it goes without saying that, due to his temerity for disseminating serious thought by humorous means, the media consistently ignores the substantive implications of his intellectual project (hence such mutually exclusive caricatures as “The Marx Brother” and “The most dangerous philosopher in the West”). What shouldn’t go without saying, however, is the thought-screening role played by his most enthusiastic fans.

Such is the level of Zizek’s popularity that, to a certain extent, the conceptual purpose of Screening Thought was structurally undermined before it even began. To meet the high demand for tickets, the sold-out theatre venue’s seating capacity was increased by supplementing it with a live video feed into the adjoining ICA cinema. This literal screening curtailed the ability of Zizek and I to engage with the audience as, to aid the cameras, we were asked to remain behind a table. More importantly, the auditorium was completely blacked out so that neither of us was able to engage with the audience’s spontaneous cues – normally a major element of what makes a live event uniquely attractive. Furthermore, because of technical difficulties in transmitting supplementary video images into the adjoining room we were limited to using just one video example of media content.

Screening Thought was bookended by two further, non-technical, illustrations of how the uncritical enjoyment of Zizek the media phenomenon undermines the message of Zizek the philosopher. The evening began with the showing of Zizek’s interview on the US TV cultural show Nitebeat. I chose this excerpt to clearly demonstrate the process whereby the media trivialises philosophical thought with benign efficiency – Zizek becomes just another figure on a chat show with a commodity to plug (a copy of The Puppet and The Dwarf that the presenter, Barry Nolan, repeatedly flourishes). The clip is undeniably entertaining but also encapsulates how for a TV audience (and some within the ICA that night), enjoyment of the spectacle risks displacing recognition of the manner in which thought is trivialized by media formats.

The evening ended with the single question that the timing of the event allowed. This was piped in from the cinema as, appropriately enough given Zizek’s psychoanalytical interests, an acousmatic, disembodied voice effusively praised Zizek and, after much meandering, eventually asked him how he dealt with his popularity.

(the question referred to was asked at 1 24:30 in the Screening Thought talk)

The fact that there was only time for one question was another popularity-induced structural limitation of the event. Although running over the schedule was not a problem in the room where the talk took place, there was a time limit to the availability of the over-fill room and it was felt by the organizers that the cinema-based audience might feel short-changed if they missed a subsequent part of the event witnessed by the live audience.

The “question” when it did arrive was more of a highly enthusiastic statement of the audience’s enjoyment of Zizek as a phenomenon rather than being any sort of considered response to the actual content of his speech. This enthusiasm can be seen as a reflecting back of Zizek’s own unalloyed enthusiasm for pure theory. Audiences have an intuitive, if at times, inchoate appreciation for the way in which his exotic subject matter and mannerisms, by contrasting so heavily with standard media fare, hint at what could possibly exist in a conceptually richer mediascape.

Whilst I may already have known at some level that audiences frequently come to experience the Zizek phenomenon rather than reflect upon the substance of what he says, I had not fully appreciated this until experiencing it first-hand. This is in keeping with one of Zizek’s favourite psychoanalytical phrases used to describe the common phenomenon whereby despite knowing something we continue to act as if we didn’t – Je sais bien mais quand même (I know very well but even so …). Literally seeing things from Zizek’s perspective (if only for a couple of hours) forced me to confront what, at another level, I was already well aware of – the manner in which his performances, irrespective of their underlying theoretical qualities, threaten to become exactly that – performances. I am belatedly now much more aware of the otherwise obvious risk that, adrift in commodity culture, Zizek’s brand of critical theory risks becoming an inadvertent manifestation of the very issues it seeks to highlight.

My introductory comments to the talk – designed to set up a broad social and political account of the context in which the media screens thought – fell rather flat, a perception later reinforced by a friend in attendance who overheard a member of the audience saying that my opening remarks had been “far too critical”. To avoid accusations of self-serving blame displacement, I unambiguously and readily accept the possibility that I simply delivered a poor talk in a manner ill-suited to the evening’s venue and format. However, whilst recognising that owning up to my personal inadequacies is likely to be a life-long project, I suggest that the talk’s relative failure points to a bigger underlying problem lurking that night within the auditorium’s almost adulatory atmosphere. A significant proportion of the audience seemingly missed the contradiction of celebrity worshipping at a talk explicitly designed to address the media’s thought-screening processes.

Until that evening at the ICA, I had blithely overlooked the extent to which the strength of the forces arrayed against critical thought may also include the unwitting contribution of its own devotees. Zizek’s thought is then squeezed between disingenuous detractors who deliberately misrepresent him and the negative consequences perversely caused by the excessively uncritical and enthusiastic reception generated by the glow of his successful media profile. Arendt’s open question assumes fresh resonance when considering how much enjoyment can be derived from a Zizek performance before our witnessing of the return of repressed thought becomes an unreflexive end in itself and a betrayal of its original radical impetus. If Zizek’s popularity does indeed represent a return of what is normally repressed it is worth looking more closely at how even audiences well-versed in critical thought remain vulnerable to those repressive tendencies that work so “normally” and unobtrusively within the mainstream media – the subject of Part Two.

Part Two of the series will be published next week.

1 Comment

Žižek Speaking at Screening Thought talk « mediologistinprague

[…] to be found in the article in Ceasefire Magazine here. Rate this: Share […]