Review: Hip-Hop on Trial Debate

Debate, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, July 13, 2012 0:00 - 1 Comment

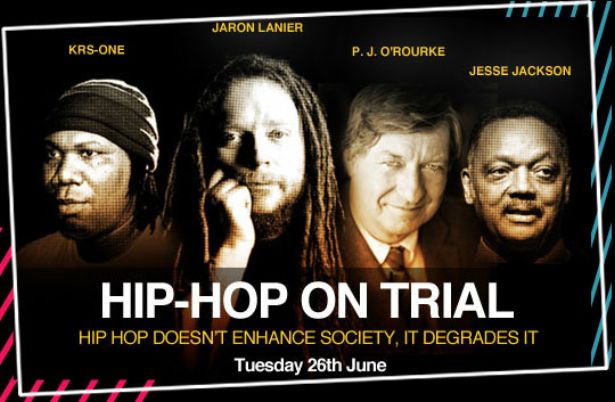

‘Hip-hop doesn’t enhance society, it degrades it’: a debate which took place last month at London’s Barbican

Two weeks ago, the Barbican hosted an Intelligence Squared debate entitled ‘HipHop on trial’, whose motion was “HipHop doesn’t enhance society, it degrades it”. The debate brought together an eclectic selection of speakers from the worlds of media, politics, music and academia.

The first contribution, in defence of the motion, was by Eamon Courtenay of the Courtenay Coye law firm, and presented a depressingly familiar response to hiphop.

Having admitting at the outset to knowing very little about the subject, Courtenay claimed he had learned some unacceptable truths from his 16-year-old daughter and recalled an instance in which, upon returning from a Ludacris concert (the urge to extract some comedy gold out of the US artist’s name was not resisted), she started reciting the lyrics, until they became too obscene to be uttered in front of her father.

This anecdote, the audience and panel were told, is being repeated across the globe, and is therefore the most compelling argument proving that HipHop degrades society. We had to feel sorry for Cournenay however, as he was followed by Michael Eric Dyson, a towering intellectual whose hiphop knowledge began on the streets of Michigan and Detroit, while his oratory skills were honed in the Black church and his academic credentials gained through his teaching posts at Brown, Columbia, Pennsylvania and Georgetown University to name but a few.

Dyson slipped seamlessly from Tupac Shakur quotations to the violence of US foreign policy and the degradation of the state school system. His response to Courtenay’s opening gambit was at once entertaining, insightful and academic.

A slightly nervous Emily Maitlis, of BBC’s Newsnight, chaired the event, in a role which we can only assume was supposed to represent some form of neutrality. The panel(s) included a multitude of guests who ranged from inane soundbite-churning government spindoctors – who effectively blamed hiphop for the existence of racist attitudes towards people of African descent – to a Fox network columnist, Jason Whitlock, who blamed hiphop for the existence of the prison industrial complex.

Tony Sewell

Shaun Bailey offered his usual mantra of self-congratulating Thatcherism – how his hard work got him where he was, and how Black people are oppressing themselves by listening to Jay-Z et al. He also predictably went through some statistics of Black boys deaths from gun or knife crime in London so far this year, and seemed astonished that the audience didn’t scream out “What shall we do Shaun?!”, as I assume he’s used to at his regular meetings at Downing Street.

Tony Sewell, writer, academic, ex-World Bank consultant and CEO of the charity Generating Genius, didn’t go down his usual diatribe of how black boys are too feminised (my guess is that this was probably because it would support an argument for the masculinity of HipHop), or that they simply lack the attention skills of their white counterparts.

Instead, Sewell attacked the language of HipHop, remarking that you can’t get anywhere in life without speaking standard English. The fact that he was arguing against Dyson, who embraces the African American vernacular in a compelling manner, and whose influence and charisma effortlessly ascend to heights Sewell could only dream of, did not appear to occur to him.

Sewell’s conservative ideology, mixed with uncritical colonial assumptions, left him sitting smugly in his own ignorance. Attacking Jesse Jackson for refusing to condemn any use of the N-word, because the Rev Jackson had ‘interest groups’ (i.e. working class African Americans), did not feel out of place despite sitting between a Conservative Party advisor and a Fox columnist (not to mention the funders of his own charity, or his ex-employers at the World Bank, which I’m sure don’t fall into the working-class African American demographic bracket).

Shaun Bailey expanded on his exhibition of naivety by announcing that he doesn’t mind HipHop portraying Black men as sexual, it’s just the violence he doesn’t approve of. Such gleeful ignorance of the legacies of slavery and colonialism only helps to re-enforce Bailey’s total misunderstanding of the politics of HipHop, race, class, and pretty much everything else.

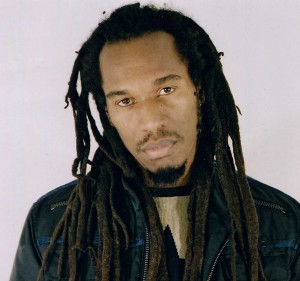

Benjamin Zephaniah

Benjamin Zephaniah

Incongruously placed on the team more critical of hiphop was Benjamin Zephaniah – African Caribbean dub poet and musician, known for his left-wing political stances, most notably when he turned down an honour from the Queen proclaiming ‘This OBE is not for me“. Zephaniah criticised mainstream HipHop, as members of both panels had done, but was quick to remark on lesser-known artists like Lowkey and Logic, who Bailey dismissed as irrelevant.

Tricia Rose, an academic known for her nuanced, rather than romantic, analysis of HipHop caught Courtenay offguard when he expected bleating agreement.

When asked confidently if she agreed with women being referred to as ‘bitches’ or ‘hoes’, she responded that, as one of the few women on the panel, she refused to being demoted to simply answering questions on gender. Courtrney’s conservative paternalism left him both uncomfortable as well as confused by Prof. Rose’s assertion.

On the other side of the panel, legendary MC Krs One began by showing humour and understanding. The arguments made by this side of the panel did not assert the same abstract moral imperatives of Bailey et al. They sought to contextualise the violence, misogyny, materialism and racialised politics within Hip-Hop. The violence of action films, the misogyny of the mainstream press and the marketisation of every sphere of public life brought hiphop out of the clouds, and crashing down to earth.

KRS-One went as far as to assert that Western society engages in illigal invasions, consumes from exploitative labour, is based on a patriarchal system of gender inequality and degrades indigenous cultures – if this is the case, he pointed out, then he was on the wrong panel, because, if this is the society we’re living in, then HipHop is doing us a favour by denigrating it.

Comments from Q-Tip, ?estlove and Estelle (with a creeping New York accent) added further artistic voices into the mix, with Estelle questioning Courtenay’s parenting skills, rather than Ludacris’s lyrics, after he admitted to allowing his 16-year-old daughter to go to a concert that he evidently knew nothing about.

Q-Tip tackled the use of the N-word most convincingly, by attempting to explain the relationship between slavery/Jim Crow, and how a population comes to terms with its legacies when it does not have the access to the educational resources that middle class Blacks have used to intellectualise and interrogate the use of the word. ?estlove supported this by citing HipHop as an avenue which led him to political consciousness.

Michael Eric Dyson, former-pastor, pointed out to the panel that the bible was full of racism and sexism yet the side of the panel critical of HipHop would hardly endorse a call for a ban on Christianity. Dream hampton, ex-editor of The Source magazine, went further in observing that, while she could challenge Dr Dre and Jay-Z about their attitude to women, any attempts to approach her pastor with a critique of misogyny in the bible would be completely rejected.

Rev Jesse Jackson supported this by pointing out the hierachies of crime and morality within society. “Poor people steal, rich people embezzle”, he remarked, highlighting the need to contextualise and account for the power structures at play both within the HipHop industry, and society at large. The debate on language came to a climax when an elderly white English professor, John Sutherland, insisted that Tupac will be studied as great American literature in 30 years time, which stopped Bailey and Sewell in their tracks, and appeared to struggle with being in conflict with the views of an old posh white man.

Although at times chaotic and frustrating, the debate was a great opportunity to see a wide range of artists, activists and writers come together to discuss a topic central to the lives of millions of young people across the globe. The debate could have lasted all evening; its resulting transcript presenting a set of texts cutting across racial, gender, class and ideological boundaries. It brought the insights of a number of leading Black thinkers to a UK audience for the first time, and we hope that the profound impact they have had on discussion of race, class and culture in the US, will stimulate a better understanding from the point of view of our own artists and analysts.

1 Comment

Sara

Sounds like it was a truly entertaining event, or a humorous and well written one.

I was particularly surprised by Sewell’s assertion that one cannot get anywhere without speaking standard English, considering that language is fluid in its nature and somehow we have all transcended from speaking and writing as Shakespeare once did. If anything, language continues to hold the same messages in similar ways with striking and enlightening parallels. We only need to compare as Akala did in his lecture at Ted X between Hiphop and Bard’s plays..

?estlove did us proud to represent countless people who have also used HipHop as the fertiliser to sprout the seeds of political and social consciousness that we all have rooted within us. It is not that we are completely unaware of the raw truths that the likes of Lowkey and Logic may rap about, but they make us and the masses somewhat uncomfortable to hear.

We’d much rather hear songs which provide us with distraction of these truths and create disillusion which keeps us cemented in inaction and self obsession.

Perhaps its time for us to become a bit uncomfortable.