Radical Aesthetics The politics of art collections

New in Ceasefire, Radical Aesthetics - Posted on Sunday, June 19, 2011 0:00 - 0 Comments

By Daniel Barnes

By Daniel Barnes

A selection of works from the Government Art Collection is currently on display at the Whitechapel gallery. The Collection is more than an archive or a celebration of cultural achievement; it is a diplomatic tool in international relations. It reveals that beneath the gloss of British politics, while there are some keen eyes for art, there is also an insidious desire to use art to exercise political power.

Collecting art is a funny business because it requires no particular skill or talent, but only a substantial reserve of cash. As the great Saatchi has always maintained, the only criteria by which one decides what to buy is whether one likes it. Of course, one might consider market value, but that is not about art – it is purely a matter of economics. As the collector, you are the sole arbiter of what is good and worthy, which means that art collections tell us a great deal less about art than they do about the collectors.

One would think that, if he had been so inclined, Saatchi could have begun a collection of Old Masters or Impressionists, but instead he invested in the emerging talent that caught his eye. Consequently, Saatchi’s formidable collection now includes some of the most important artworks of the last two decades. As such, the Saatchi Collection documents a vivacious period of art history; but these works would do that anyway, no matter where and by whom they are collected.

What the Saatchi Collection does is reveal an insight in to the intensely private individual Charles Saatchi: it reflects his personal taste in contemporary art and maps out his various affections for individual artists; it tells us that Saatchi is a risk-taker, someone who doesn’t shy away from controversy, and above all a man who thrives on the new, who is passionate about the very cutting edge of art.

The British Government has been collecting art since 1898, in which time it has gathered a collection of 13,500 pieces. Like all collectors, the Government has its own personal criteria for deciding what to buy, but unlike many collectors whose guiding light is simply personal taste or commercial value, the Government has a complex and sometimes unsettling network of motives.

The acquisitions policy of the collection is motivated by a concern to promote British art and artists in the name of ‘cultural diplomacy’. Only one third of the collection is held in storage at the Tottenham Court Road HQ, while the remaining two thirds are on display in embassies, consulates and other British government buildings in all corners of the world. The collecting remit is driven less by a matter of taste or economics than it is by an act of ideological posturing that aims to show off and assert cultural heritage to the nations and territories in which the United Kingdom feels it has a legitimate presence.

The role of art in this context is a political one insofar as the Government Art Collection is playing on the notion that a culture can be judged, not by its political actions, but by its contribution to the global culture industry. Consequently, whilst the Collection does contain some noteworthy works, it often sacrifices solid artistic or historical value for the instrumental purpose of conveying a particular message of political weight to foreign powers.

The works seem to fall into two broad categories: representations of British life and events in the history of Britain’s international relations; that is, either ‘we are better than you’ or ‘we tried to own you’. The British Embassy in Beijing is awash with William Alexander’s engravings of Chinese landscapes from his ‘An Authentic Account of An Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China’.

The British Embassy in Havana is treated to a history lesson with Dominic Serres’ painting The Capture of Havana by the English Squadron. The British Embassy in Baghdad gets a reminder of its occupier’s royal grandeur in Robert Tavener’s painting of St James’ Palace and patronised with scenes of mosques and Middle Eastern dwellings produced by the likes of Joan Williams and Edith Florence Cheeseman. So not only are the artworks that we display in foreign countries ideologically loaded in their selection and positioning, they are also – to be brutally honest – really quite dull, as if we spend taxpayer’s money on art for the world and refuse to share it around.

It is not surprising, then, that the very best works tend to hang in government buildings at home. By the ‘very best’ works, I mean those with the greatest art historical significance and those which are among the most aesthetically profound. For instance, the HM Treasury sports a very fine collection of Gary Hume portraits, which, even if not to everyone’s taste, are crucial milestones in modern British art. The Home Office is a seductive advert for great British art, with works by Turner nominees George Shaw and Liam Gillick. The British contribution to pop art is documented at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport by a full set of Peter Blake’s alphabet screenprints.

The Government Art Collection, however, presents a problem for the view that collections tell us something enlightening about the collectors, since ‘the Government’ is an entity of perpetual succession that changes its internal constitution as the individuals who comprise it change. But like the Ship of Theseus, the Government ploughs on throughout history with the same mission and purpose, no matter how many of its rotten planks are replaced.

Born in the last days of the Empire, the Collection was designed by a government who aimed to assert its sovereign authority over others, which is a mission it has still not given up today. Wherever the British Government lays its hat, it covers the walls in art in order to cling to the dying threads of cultural imperialism, as if visiting dignitaries will bow to art as they once did to generals and governors. It is also noteworthy that the absence of works from the Collection equally makes a compelling political statement: Jerusalem and Kabul are denied any art at all, sending out a message to the ‘enemy’ that, until they learn to play nice they shall not get any pretty pictures to look at whilst visiting one of our embassies.

The selection currently on display at the Whitechapel is interesting because the works are selected by current and former ministers, ambassadors and civil servants, revealing a vast difference between political and aesthetic stances. The harmless but idiotic Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg, shows that whilst he cannot stick to a policy in the face of a fancy office, he can recognise a beautiful moment in art history, captured by David Dawson’s photograph, Lucian Freud Painting the Queen. And Ed Vaizey, who currently sits at the helm of the bulldozer that is driving through arts funding, reveals a keen sensitivity to edgy contemporary art by choosing works by Tracey Emin and Michael Landy.

The role of the Government Art Collection is to mediate between the soulless political institutions that claim sovereignty over individuals and the cultural ties that bind people together. The personal selections of ministers at the Whitechapel humanise those who clutch our lives in their hands, and the works in embassies around the world attempt to gloss over complex political realities.

Art is used to anesthetise, so that citizens may be more susceptible to being put in their rightful place. It is, then, not about art at all; the Government collects art because it has this seemingly innocuous but ultimately perverse notion that where politics divides, art unites.

Daniel Barnes is a philosopher and art critic based in London, UK.

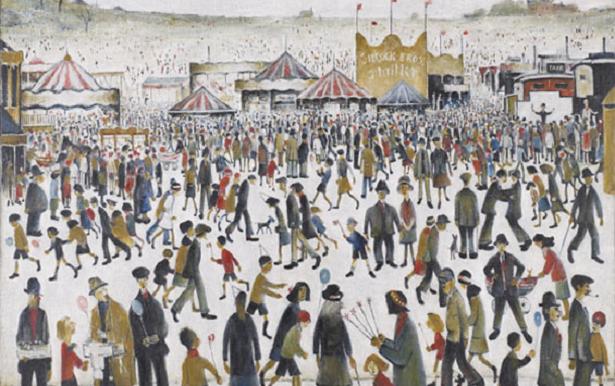

Image: L S Lowry. Lancashire Fair. Good Friday. Daisy Nook . 1946. Oil on canvas; 72 x 92 cm © The Estate of L S Lowry, 2010/courtesy of the UK Government Art Collection.

Leave a Reply