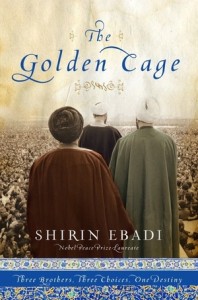

Books ‘The Golden Cage’ by Shirin Ebadi

Books, New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Thursday, June 30, 2011 9:00 - 1 Comment

By Frederick Andrews

By Frederick Andrews

As Shirin Ebadi argues on the back of this masterpiece, ‘history is best described through life stories that are told in simple ways by appealing to what human beings hold in common, the love of life and country.’

Indeed, this book itself is testimony to such a claim, with its depiction of an Iran seen through the eyes of someone who has not only been at the heart of its history, but who has fought and achieved so much for her fellow compatriots in recent years.

Shirin Ebadi, author of The Golden Cage, deserves some introduction. Born in Hamedan, Iran, and educated at the University of Tehran, she has worked as a judge, a human rights activist and a lawyer. In 2003, she became both the first Iranian and the first Muslim woman ever to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, for her tireless efforts for democracy and for human rights.

Now living in the United Kingdom, as a direct result of the increase in the Iranian government’s persecution of those critical of the regime, she has written her memoirs in order that we might catch a glimpse of mid 20th century Iran, and once intrigued by the author’s childhood, we might become similarly embroiled in the struggles faced by her and those around her.

She invites us to watch, as present-day Iran is forged from regimes of old. The publication of The Golden Cage, striving as it does to uncover a slice of the ongoing oppression in the country, is symbolic of Ebadi’s struggle against those who once ruled, and those who currently rule her homeland. In it, she reminds us of how most current events are in some way deeply rooted in the past, and how Iran’s political events are in no way an exception.

The events of the book are centered around the three brothers of a close friend. Ebadi retells the tragedies of their lives, and uses their stories to symbolise, as she sees it, the fundamentalist ideologies that are responsible for tearing her country apart.

As each brother grows up, he locks himself in his own golden cage, so to speak, as the pursuit of his beliefs about how his country should be run slowly isolates him from family, friends and even lovers, ultimately bringing about his demise.

The first brother, a staunch monarchist, swears by the name of Reza Shah, the last of the Pavlavi dynasty to rule Iran. The second becomes involved with one of Iran’s earliest revolutionary groups, the Tudeh, whilst the youngest brother devotes himself to the religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini, who headed the 1979 revolution that toppled the Shah and gave birth to the Islamic Republic of Iran.

As Ebadi watches the events unfold in the lives of those around her, so she inserts anecdotes from her own life, and history lessons that adhere to her maxim of simplicity, all of which holds together what is ultimately an incredibly well-structured work.

The insight we are given into the rich cultural beauty of Iran is delicately crafted from nostalgic childhood memories, heavily poetic language, rich in scents and tastes. However, the fragility and innocence of these depictions also means that they serve as a perfect backdrop against which the sorrow and loss of the story is set, as all that is held dear by the author is swept away by the unwavering ruthlessness of successive regimes.

The “Islamic Revolution” of 1979 is the pivot around which the tales of the three brothers are centered. Through her work, Ebadi’s nationalist views shine like the beacon of hope that she clearly has been for Iran.

That she was eventually ousted from the country due to her humanitarian and judicial work, as well as the danger of her position as a writer, serves only to enforce her devotion to the cause at hand, and to set her apart from the three brothers’ visions for her country.

She tells of how, initially, she supported the revolution, and saw the end of the tyrannical reign of Reza Shah as potential for hope. However, the days of protesting in the streets are soon left behind, as it becomes ever clearer that the Shah’s successor will serve her compatriots no better.

Ultimately, it is a love of Iran that pervades the book; a love that withstands great loss and sadness, and one which is perhaps even more tangible given the semi-detached status as narrator that she takes.

The work is nothing if not modest, and to describe it as memoirs could potentially be misleading. Little is made of the author’s own work and actions. Rather, Ebadi lets the pure factual events of the brothers’ lives do the talking. What little we learn of her is that she, like her friend Pari (the sister of the brothers,) did whatever she could to make life easier for those around her, and seems not to have judged any of them for the paths they each decided to take.

The book’s greatest triumph, though, comes arguably from the masterful way in which the notion of women in Iranian society is dealt with. The repression suffered is understated if anything, but the impression given is that this is deliberately, and cleverly, so. The phallocentricity of Iranian society is clearly marked by the undeniable focus on the brother/ideology symbolism, and indeed by the early chapters depicting the upbringing of the family, and the influence on all four siblings’ formative years of the father, Hossein.

However, Ebadi carefully composes the work so that the importance of the female characters goes largely unacknowledged by their male counterparts. It is the reader, who is blessed with an unblinkered understanding of all the intertwined lives and motivations captured by the book, who is able to fully comprehend the key roles played by Ebadi, her friend Pari, and their mothers.

One is forced to pity the female characters, who whilst underpinning the events to an extent, are left behind by the selfish actions of those of the privileged sex. Pari is left with a shell of a family after all three brohers fly the nest for their separate reasons, and Ebadi recounts how she frequntly became a source for comfort, company and help in the aftermath of the devastation inflicted on the family.

Despite this subtle yet poignant focus on the importance of women, Ebadi seems careful not to make of her book a feminist tract. Given the potential in her subject matter, such restraint is impressive yet, in some way, absolutely fitting.

The Golden Cage is truly a masterpiece: a collation of personal memories, encounters and stories that have been combined in a way that makes for an easy reading. Ebadi’s work shelters no ulterior motives, but rather a beautiful innocence of writing in which all that is meant to be conveyed or inferred is readily accessible, yet never in a way that is patronising or sermonising.

A balance is thus struck so that even a reader with limited knowledge of contemporary Iranian history will come away from the book with a firm grounding and, hopefully, a realisation of the true nature of the problems facing the country today, and how they came to be.

The Golden Cage: Three Brothers, Three Choices, One Destiny

The Golden Cage: Three Brothers, Three Choices, One Destiny

By Shirin Ebadi

Hardcover: 256 pages, RRP £19.99

Kales Press (17 Jun 2011)

Frederick Andrews is a Ceasefire contributor and a student at the University of Oxford.

1 Comment

How I deal with it | I was born and raised

[…] for something. I’m watching Egyptian music TV shows, Hong Kong movies, and Hindi movies, and reading Irani books because i’m existentially lost. I’m triple and quadruple translating words and phrases for […]