An Anthem of a Revolution That Was — A Revolution That Will Be: ‘The City Always Wins’ by Omar Robert Hamilton Books

Arts & Culture, Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Sunday, November 12, 2017 10:47 - 0 Comments

By Ahmed Masoud

If I didn’t have to write this review, I would probably have never finished reading The City Always Wins, by the talented Omar Robert Hamilton. Instead, I would have carried the book with me everywhere, keeping it by my bedside and reading a passage or two at a time, leafing through the pages at random; as if putting my favourite music playlist on shuffle mode. There are very few books that have had such an impact upon me — Pascal Mercier’s Night Train to Lisbon comes closest, but Omar’s debut effort certainly wins that lyrical contest.

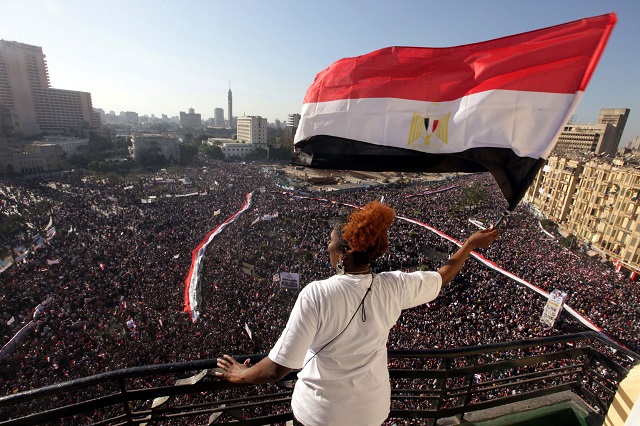

The City Always Wins is a tale of the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution of January 25, 2011, and the ensuing quest for democracy, told through the lens of a group of revolutionaries driven by faith in a better future for their country.

The book presents a fascinating insight into the green room of the revolution, and the challenges it faced. We all know how those events unfolded, or maybe we think we do. The dishonourable pact between the army and the Muslim Brotherhood against the revolution is a pivotal milestone in the story; yet it’s something many outsiders might have missed amidst the cacophony of media coverage. As a spectator of the events myself, I had little notion of that the Muslim Brotherhood — these ‘dictators in waiting’ — were leading Egypt into another period of darkness. Even though I disagreed with the MB’s politics, and their quest for ultimate power, I had failed to notice the extent to which they were derailing the revolution and, in so doing, paving the way for the army to take back control.

Someone who did see all of this is Khalil, the prophetic, American-Egyptian central character of the book. In the delirious euphoria of the events of 30 June 2013 — General Sisi’s summer coup, and Morsi’s downfall — he saw what was going to happen next: ultimate powers back in the hands of the army.

The book offers a remarkable cast of characters, all of whom essential to the unfolding of the story: From Miriam and Khalil, young revolutionaries whose romantic entanglements are a central axis of the plot: Alaa, the political prisoner; Hafez, the martyr; Abu Bassem, the ordinary father of another martyr; Um Ayman, who lost her son in the revolution; a nameless doctor… who all come together in compelling tableaux of hitherto-unheard ordinary citizens living through extraordinary circumstances. Suddenly, the abstracted statistics of news coverage are transformed into real voices which, in turn, re-emerge as full, human lives and experiences:

“She thinks, every morning, of the way he would prepare the cheese for breakfast. Ayman, her boy, her Ayman, and his moment of pride and presentation to the family everyday. The soft whiteness scooped out of the packet and spread with a swirl in the shallow bowl, the herbs – zaatar usually, mint sometimes…But she cannot shake the thought. That he was hungry. Why did we not eat together? Were we all so consumed with the news? Her boy died hungry. He went out like a man to stand up for his people and his church and his family and he marched, and marched hungry. Don’t worry. She can hear his voice perfectly. I will eat, I promise. Don’t worry, Mama.”

As part of their ‘Chaos Cairo Collective’, Miriam and Khalil are pioneering media reporting of the revolution, documenting protests as they happen and collecting testimonies from those tortured or imprisoned by the regime. Through the eyes of these observers — Miriam, Khalil, Hafez, Alaa, Rosa — readers are able to catch raw glimpses of the inner, chaotic life of the revolution. We watch as they cheer the fall of Mubarak; disagree over leaving Tahrir Square; are outraged at the Muslim Brotherhood’s ploys; urge people to protest against Morsi’s darkening reign. And then, all of a sudden, Murphy’s Law starts to unfold in front of their eyes. Within two years, the army has taken back control and they have become, once again, the hunted; chased, one after the other, like ‘wild dogs’.

Writing about recent history — about events that are five, or even ten, years old — is never easy. Such close historical proximity tends to make for uninteresting literature, mainly because, as readers, we are in many ways still living through them, and yet to see their full, lasting impact. Hamilton pulls it off, however, and does so, in large measure, by presenting every one of these events through the prism of the same, central question: “What If?”

What if the revolutionaries had taken over the Maspero Television building? What if Khalil hadn’t run away from the police and, thus, ended up in prison? What if the martyr hadn’t gone to Tahrir Square on that fateful morning? What if the Muslim Brotherhood hadn’t acted so stupidly in conspiring with the army against the people? What if the Left’s energies hadn’t been so needlessly divided between two candidates at the presidential elections?

Of course, ‘What if’ continues to exert its spell on all of us observers of the ongoing events of the ‘Arab Spring’. What if the revolution in Egypt had succeeded in extending the democratic tide across the wider Middle East? What if the Syrian conflict hadn’t turned into the bloody and devastating catastrophe it is now? What if all those Western-made dictators had vanished? For that matter, what if the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ had never happened in the first place?

These questions are yet to be answered. In the case of Egypt, our collective imaginations seem barely able to come to terms with the realities of the new military order; many of which are described with lucid starkness throughout The City Always Wins: The never-ending cycle of arrests, the massacre of the Muslim Brotherhood protesters in the summer of 2013, the arrest of Alaa and Rosa, and many others from the ‘Chaos Cairo’ Collective.

And this, strangely enough, is the trouble with Hamilton’s novel. Put plainly, it seems to present the Egyptian revolution — or the various strands within it — with a relentless romanticism I’m not sure really works in its context. Moving along the well-crafted lyrical passages and monologues of the book, I couldn’t help but picture myself in some theatre, watching a musical production of Les Miserables (perhaps because Hugo’s original opus, was itself about another, much-celebrated revolution), and soon belting out “There’s a grief that can’t be spoken, there’s a pain goes on and on; empty chairs at empty tables now my friends are dead and gone.” When Khalil goes into the Stella Bar — after the army had taken over, and images of Sisi filled the streets outside — I half-saw the lines, “Here they talked of revolution, here it was they lit the flame, here they sang about tomorrow and tomorrow never came” appear on the pages.

The Revolutionaries in The City Always Wins are unabashedly idealised — another Les Mis echo — as is their quest for a better future for their country. Khalil goes into endless soliloquies about the emptiness and savagery of the world around him, yet never seems to delve that deeply into a discussion or debate of the central questions, such as why the Egyptian Left had been so fatally divided. Yes, mistakes were made, the novel seems to concede through its portrayal of the revolutionaries’ decision to support two Left candidates — which ceded the terrain to the Army and Muslim Brotherhood — but the book doesn’t really address or invoke other unification attempts by the Left. Had the elections not taken place so soon after Mubarak’s downfall, could there have been a different outcome? One in which, perhaps, the Brotherhood never got in in the first place?

The novel’s overarching thesis, namely that the conflict between the army and the Brotherhood is the reason why the revolution failed, perhaps explains its romanticisation of the Revolutionaries. Such idolising of Khalil, Miriam and their fellow comrades, however, might strike some readers as a little too credulous. On a personal note, as a Palestinian and a member of the Palestinian literary revolution, I believe it is crucial for us on the Left to discuss, as openly as possible, the key issues that divide us before attempting to take on the ‘other side’ and their shoddy deals and conspiracies.

It is beyond doubt that The City Always Wins is a book that takes the conversation around the Egyptian revolution to a more profound level than any before it. It makes it clear that this is not about a particular group or religious creed but, as the title suggests, about the city itself. In a final act of rebellion, Miriam and Khalil place their FM transmitter outside Tora Prison, in order to broadcast to their fellow Revolutionaries incarcerated within the news from the outside world:

“This is a special broadcast for Tora Prison. We will not stop working until you have your freedom. We are sorry that we are not strong enough to get you out yet, but we will. Coming up in this broadcast after the news of Sisi’s economic and political failures we have world news, new music and notes from the cinema. Stay tuned until they work out how to shut this transmission down…”

It’s a powerful scene, and offers a striking reflection: that Cairo will always rebel against its tyrants; that there will always be someone, out there, protesting; that there will always be a revolution around every corner. That what happened in Tahrir will continue to propel the city’s revolutionary spirits for a long time to come.

Omar’s novel also brilliantly presents the issue of women’s harassment for what it really is, an endemic problem. His decision to highlight anti-harassment vigilantes operating during the protests in Tahrir offers an honest account of an uncomfortable facet of the Tahrir story. The revelation that the Muslim Brotherhood, once in power, adopted and deployed the Mubarak regime’s harassment techniques against women to deter them from protesting is a startling one. This is an especially important issue to highlight because it remains very much part of Egyptian women’s lived realities; only a few months ago, Cairo was named as the worst city in the world for women to live in. In this light, Hamilton’s foregrounding of strong female characters is admirable, and offers readers a portrait of the revolution’s many strong, empowered Egyptian women — women who have remained largely unheralded since, and who continue to struggle against a deeply misogynistic society.

“So we will swap Mubarak for Tantawi for Morsi for Sharon for Obama for whoever, swapping them in one after another as we write long books and argue into the night about “the people” and what we think they want. We will do it the few more times left to us before the world finally falls to the fever that will rid it forever of our bacterial civilisation. Or we do the one thing we haven’t tried yet, the one thing that might just change everything. The time is now, the people are ready: the only revolution left is a women’s revolution. Tomorrow we say “enough” . Every woman will stop working, managing, maintaining the world and we watch it crack at the seams. It’s the only thing we haven’t tried”

I have no doubt that I will be reading The City Always Wins over and over again for years to come, soaking more of those beautifully written pages and admiring a tale of a city that is rebelling every day — a city where events can go from success to failure in a single moment — and, whenever things in the city change, as they are bound to, I will revisit the book in search of those prophecies I had missed the first time round.

I have no doubt that I will be reading The City Always Wins over and over again for years to come, soaking more of those beautifully written pages and admiring a tale of a city that is rebelling every day — a city where events can go from success to failure in a single moment — and, whenever things in the city change, as they are bound to, I will revisit the book in search of those prophecies I had missed the first time round.

The City Always Wins

Omar Robert Hamilton

Published 03/08/2017

Length 320 pages

ISBN 9780571335176

Format Hardback

Leave a Reply