Rotoscoping: A Promising Art Arts & Culture

Arts & Culture, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Sunday, November 20, 2011 20:05 - 6 Comments

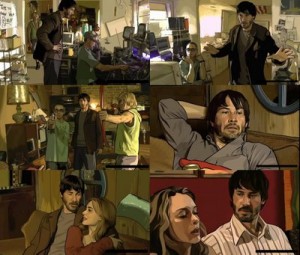

An example of how rotoscoping take its form, from A Scanner Darkly (2006)

Rotoscoping, the art of animating on top of live-action film, is a deceitful art form. By incorporating both live-action footage and animation, a rotoscoped film refuses to align itself with either – yet masquerades as both. Live-action is associated with reality as the camera has observed real objects that would be there even if it were not. Animation is intrinsically fantastical as its objects have been created by an artist, even if they mimic reality.

What is so interesting about rososcoping is that the reality of live-action and the fantasy of animation do not meet – they overlap, ingrained in its fabric.

The primary function of rotoscoping is to utilise the double identity created by experiencing live-action and animation simultaneously. As a rotoscoped film is always part-real, part-imagined, either aspect can be emphasised at the filmmaker’s will by foregrounding the film’s live-action or animated side.

Thus the medium’s potential lies in toying with the balance between the two. Combining the real and fantastical in this way allows a film to flitter from reality into fantasy without obvious ‘special effects’ markers that, despite their credibility, stand outside the live-action. The technique opens up many possibilities, but it also means that a rotoscoped film is never truly realistic nor fantastical.

The animator Norman McLaren wrote: ‘Animation is not the art of drawings that movement, but of movements that are drawn.’ When we consider film in fundamental terms, animation must rank among its most creative forms. The clue is in the name, which means ‘the act of giving life or spirit to something’.

The film camera captures a pre-existent reality; in animation, by contrast, every cinematic events is wholly given birth to – ‘animated’ – by the artist. All aspects within the frame have to be orchestrated.

Rotoscoping, of course, is not just animation alone. The movements that are drawn as part of the rotoscoping process have not been created so much as recast, as the live-action footage that precedes them acts as a platform from which animation springs. In other words, the rotoscoper’s canvas is not blank – it already has lines drawn on it.

Should they desire, the animators can disregard the lines that give the frame its basic shape, keeping only the most essential of forms (or losing them entirely).This ability gives the animator free reign over to what extent reality’s borders are to be respected, as the further the original form is deviated from, the deeper into the unreal we go. Conversely, the contours of the frame may be accurately adhered to, the result of which is uncannily realistic. When the live-action’s every details are mimicked any solid distinction between the filmed and the drawn is erased.

A screenshot from Thomás Lunák’s recent film Alois Nebel (2011)

A film can be rotoscoped either by hand or machine. As you might expect, hand-rotoscoping is exceptionally time-consuming, potentially resulting in over 100,000 individual drawings for a feature-length. For Czech graphic novel-cum-film adaptation Alois Nebel (2011), each character in the film had their own animator; no single frame was used twice.

With no intention of animating the film prior to the shoot, the action was shot in 35 days. Upon completion it was decided that the film would stay true to its original graphic novel form and be animated in a black-and-white noir style. Deciding to rotoscope by hand – a lengthy process – meant the film was not completed for another five years.

In this case rotoscoping was used so that the graphic novel’s distinct style would not be lost, opting to precisely and realistically set an animated book in motion. The clip above shows how rotoscoping helps craft the film’s dramatic feel.

Alternatively, software such as Rotoshop may be used. A programme developed by computer scientist Bob Sabiston, Rotoshop makes the process drastically less time-consuming by reducing the amount of frames the animators must hand-draw. In order to do so, computer-generated frames slot between those drawn by hand. The interpolated frames are generated as the programme identifies the mid-way points of two drawn frames. Interpolated rotoscoping plays the role of illusionist, inserting itself with no discernible difference between what was achieved by man and by machine.

Alternatively, software such as Rotoshop may be used. A programme developed by computer scientist Bob Sabiston, Rotoshop makes the process drastically less time-consuming by reducing the amount of frames the animators must hand-draw. In order to do so, computer-generated frames slot between those drawn by hand. The interpolated frames are generated as the programme identifies the mid-way points of two drawn frames. Interpolated rotoscoping plays the role of illusionist, inserting itself with no discernible difference between what was achieved by man and by machine.

American filmmaker Richard Linklater has made two feature-lengths that use Rotoshop. Waking Life (2001) was the first: a non-sequential journey through one of our protagonist’s dreams. Along the way, we encounter a series of characters who, like in Waking Life’s precursor Slacker (1991), do not so much impart wisdom as explore existential themes. Topics include the philosophy of language, the evolution of ethics and the question of what it means to dream.

An example of how rotoscoping can drastically deviate from its original frame.

In Waking Life, we are constantly reminded of the film’s fantastical nature because of the style of its rotoscoping. Our understanding of reality is questioned both philosophically and visually as no respect is paid to its boundaries, with objects and theories seldom appearing as they do in this world. Waking Life deviates with ferocity from its filmed footage, displaying an almost total liberation from it.

The style of animation varies from character-to-character, scene-to-scene. Some characters appear realistic, other not. Occasionally objects exist for our benefit but not in the consciousness of the scene’s characters. In the truest sense the footage acts as a platform from which a fantasy environment springs out, the animation’s unfettered nature assuring Waking Life’s place as a uniquely surreal film.

The second film Linklater made with the help of Rotoshop was A Scanner Darkly (2006), a dystopian tale of pandemic drug addiction. Like Blade Runner (1982), Total Recall (1990) and Minority Report (2002); A Scanner Darkly is based on a novel by the late American science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick. With a cast including Woody Harrelson, Winona Ryder, Robert Downey Jr., and Keanu Reeves, Linklater this time used rotoscoping to realise the hallucinogenic effects of Substance D, the highly addictive narcotic people are hooked on.

The second film Linklater made with the help of Rotoshop was A Scanner Darkly (2006), a dystopian tale of pandemic drug addiction. Like Blade Runner (1982), Total Recall (1990) and Minority Report (2002); A Scanner Darkly is based on a novel by the late American science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick. With a cast including Woody Harrelson, Winona Ryder, Robert Downey Jr., and Keanu Reeves, Linklater this time used rotoscoping to realise the hallucinogenic effects of Substance D, the highly addictive narcotic people are hooked on.

Unlike the previous films mentioned here the primary function of rotoscoping is to allow an effective depiction of the book’s hallucinogenic effects. It is not used for style or to give the film a surrealistic air. For those that have seen Terry Gilliam’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), the result of manifesting intoxication in live-action may lack credibility, the truth of the camera somehow at odds with the outer-worldliness of hallucinogenics.

In A Scanner Darkly, rotoscoping is used to realise specific scenes that without it would harbour clear and lacklustre distinctions between a sober reality and high fantasy.

Yet in A Scanner Darkly the moments reality’s borders are transcended are surprisingly few and far between. The majority of the film – in dystopian fashion – takes place in a realm hardly removed from our own (“Seven Years From Now”, the film declares). This, coupled with the famous faces of the film’s main characters result in the majority of the film appearing ultra-realistic. There are moments in which it is almost impossible – almost – to detect the animator’s craft.

Yet in A Scanner Darkly the moments reality’s borders are transcended are surprisingly few and far between. The majority of the film – in dystopian fashion – takes place in a realm hardly removed from our own (“Seven Years From Now”, the film declares). This, coupled with the famous faces of the film’s main characters result in the majority of the film appearing ultra-realistic. There are moments in which it is almost impossible – almost – to detect the animator’s craft.

The technique is then used to give the filmmaker a greater degree of control over the finer aspects of a frame. Rotoscoping afforded Linklater the privilege of precision over minute details such as facial expressions, backgrounds and tints. The face can be manipulated post-filming so that particular emotion is emphasised or played down (achieved by altering the shadow or movement around the eyes); unimportant objects can be edited out, and hazy coloured tints can be overlayed to give an extra layer to the film’s on-edge feel.

When used as such, the idea is that roscoping allows live-action’s boundaries to be seamlessely transgressed. ‘Special effects’ are not so much intermittently implemented as continued. The viewer is conditioned by the precision of the rotoscoping to conceive of the film as somewhat realistic.

When used as such, the idea is that roscoping allows live-action’s boundaries to be seamlessely transgressed. ‘Special effects’ are not so much intermittently implemented as continued. The viewer is conditioned by the precision of the rotoscoping to conceive of the film as somewhat realistic.

If such status is achieved, fantastical elements such as hallucinations can be drawn in in a much subtler fashion than other techniques such as more traditional CGI. The result is – paradoxically – a more realistic depiction of fantasy, creating conversions of novel to film that are truer to the original, and more believable.

In the scene below, for example, peripheral character Freck envisages what might happen were he to be pulled over by the police car behind him. Rotoscoping shares his paranoid vision with us without forcing the viewer to fill in the gaps, nor visibly deterring from the film’s style. The foray into the fantastical exits as subtly as it entered.

What I find so alluring about rotoscoping – and indeed, why it is the master of animated deception – is the way in which it enables such a fluid interplay between fantasy and realism. If there is an ever-mutating bond between live-action and animation, then no fixed understanding of where a film stands in relation to reality can be made. Rotosoping’s very essence allows – even encourages – deviation from its original frame, and yet the original frame is always there to return to it. As such, the process offers infinite possibilities while remaining anchored to the real world.

It has, then, a very practical usage that surpasses mere stylistic device. We undoubtedly class rotoscoped films as animations, but their indebtedness to and reliance on live-action is equally as visible. An opaque layer we can identify but not remove, rotoscoping can emphasise certain aspects of a film – either in a close-up of a character’s face or by adding removing objects in the background – with the most subtle of alterations. In this sense it is useful not just to those seeking to convert science-fiction or graphic novels into films, but anyone interested in being able to have another layer with which to work in.

Is rotoscoping used to make live-action less realistic or animation more so? In truth it can do both at any moment, but is no slave to either task. Rotoscoping has no boundaries, but it does have guidelines. Whatever the relation, it is its uncertainty – the joy of illusion and deception – that lie at the heart of this fantastic medium.

6 Comments

Rotoscoping Examples | NoahSteppe

Rotoscoping Technique | drifterloisbain

[…] Arts & Culture | Rotoscoping: A Promising Art […]

learning to rotoscope day 1 « veryisabel

[…] was understand the mechanics behind it all. It is truly a unique artistic practice. It incorporates live action and animation, yet struggles to be defined as one or the other because of that intrinsic […]

learning to rotoscope day 35; Summary « veryisabel

[…] movie. Rotoscoping was used by many Disney films, to create the seamless movement of animation, and encourage deviation from the original footage, while simultaneously remaining anchored to the real […]

[…] Brennan Douglas. Rotoscoping a promising art. November 20, 2011 – Link […]

3D Graphics: A History – 3D Modeling MDU115 Blog (DUB11660)

[…] Brennan, D. (2011). Rotoscoping: A promising art. Retrieved 20 October 2016, from https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/rotoscoping-promising-art/ […]

[…] https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/rotoscoping-promising-art/ […]