Walter Benjamin and Critical Theory An A to Z of Theory

In Theory, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, April 4, 2013 0:00 - 7 Comments

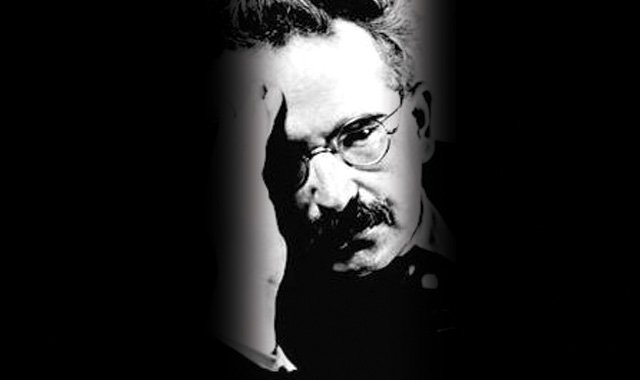

Walter Benjamin stands out as one of the leading theorists of the 1920s-30s wave of Marxist-inspired critical theorists. Like many of his generation, Benjamin writes from the standpoint of an outsider. His story is also a tragic one. Having already fled Germany for France, Benjamin killed himself after being captured by the Nazis while trying to flee occupied Europe. In his lifetime he wrote one book, the vast Arcades Project notes, and a large number of intriguing fragmentary writings which have inspired and puzzled scholars and radicals ever since.

Benjamin worked at the intersection of Marxist cultural theory with qabalah, a mystical variety of Jewish theology. Practitioners of qabalah believed that the messianic dimension cannot be reached in the mundane world. They sought limit-experiences through meditation, prayer and asceticism. Within Marxist theory, Benjamin was pulled between two schools of Marxism: the abstract ‘high theory’ of the Frankfurt School, and the more down-to-earth strategies of consciousness-raising pursued by Bertolt Brecht.

Scholars and students are most likely to have come across Benjamin via one of his short works, such as “On the Concept of History”, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, “Critique of Violence”, or “The Task of the Translator”. These texts are widely used in cultural studies, although appreciation of Benjamin’s radical politics is uneven.

Many of Benjamin’s works take the form of travelogues, in which he recounts his impressions of particular places. These are like reports on flânerie, the practice of wandering aimlessly in public places which Benjamin celebrates. Others are cultural criticism, dealing with specific texts. His longest works deal with particular areas of literature – baroque mourning-plays, Goethe, Baudelaire, and so on. He also wrote large numbers of short articles and fragments, many of which are so full of profound, ambiguous statements that they have been interpreted endlessly. Benjamin’s work is typically fragmentary, and has a kind of mosaic or montage structure based on juxtapositions.

In politics, he frequently focuses on the issue of sovereign violence. He is a major influence on Agamben. He seeks to design a materialist alternative to religious redemption and profane power-struggles. Across various works, he portrays capitalism and the state as a religious or metaphysical system based on fate and guilt. Benjamin writes mainly within a Marxist tradition, and some of his work has disciplinary overtones. However, his ‘orthodoxy’ clearly declined over time, and his main interest is in claiming expressive emotions for the revolution.

He is unusual in that he actually failed his exams by being too smart for his examiners – a claim which for most, is a handy excuse! Students wishing to emulate this performance might be interested in Benjamin’s instructions for authors. He is also notable for the argument that things or objects have some kind of language, perception or subjectivity. In an early text, he suggested that things propel us into the future.

Benjamin is one of the founders of cultural studies. Much of his work focuses on material from outside the main canon of literary studies – whether this be unrecognised literature like the German baroque plays, or popular culture such as newspapers and flyposters. Along with contemporaries such as Bloch, Adorno and Gramsci, Benjamin pioneered the view that the study of culture should not focus mainly on ‘great’ works. Everyday, popular cultural works – from mass-market paperbacks to the layout of streets and the content of adverts – are important in understanding the history and politics of culture. This makes Benjamin one of the co-founders of modern cultural studies, as distinct from the older forms of artistic study.

This position is often parodied by conservatives as the claim that “the latest advert is as great as Shakespeare”. This misses the point. The argument is not that these works are as beautiful or historically lasting as ‘great’ works. The idea of inherent value is alien to many cultural studies authors, but most continue to prefer thoughtful, erudite works. The reason for the study of what conservatives see as ‘low’ texts is that the criteria of aesthetics are replaced by an emphasis on the social and political importance of cultural texts.

Benjamin’s Method: The Epistemo-Critical Prologue

Benjamin’s first major work, and only completed book, was his work The Origin of German Tragic Drama. This was originally his dissertation for a postdoctoral degree, which would qualify him to teach in German universities. He was failed because nobody could understand it!

The work is an analysis of German baroque theatre in the 16th and 17th centuries. Instead of focusing on ‘great’ baroque authors such as Shakespeare, Benjamin focuses on relatively unknown German writers whose work was widely rejected as aesthetically inferior (partly because of its crudity and violence). Benjamin wasn’t interested in the quality of the work, but in what it said about German history and society. He saw them as creating a new genre, distinct from classic tragedy and connected to the issue of sovereign violence. He argues that this work converts history from a question of Christian eschatology (ultimate destiny or meaning) into a power-struggle, as in Realist IR theory. The trauerspiel or mourning-play is seen as a new type of drama created in the baroque era. It is allegorical, and uses a form of time which is more musical than dramatic. Its unresolved relationship to time is peculiarly modern.

The issue of the baroque for Benjamin focused on questions such as why extravagant allegories were so common at this point, and what the satisfaction was in ‘mourning’. He argues that there is a relationship between baroque and the Protestant disconnection of worldly actions from salvation (Luther’s view that faith alone determined salvation). This view also reflects the transition to capitalism, which drains the world of meaning. This disconnection disenchants the world and causes melancholy (depression). The world becomes a stage and a coffin because it is disenchanted. Mourning plays mourn the transition to capitalism. The only remaining hope is that meaninglessness can itself be redemptive.

In the introduction to this work, the Epistemo-Critical Prologue, Benjamin lays out the approach to research which guides his later work. Benjamin advocates a method which lacks an ‘uninterrupted purposeful structure’, relies on digression, and constantly re-thinks new beginnings by returning to its goal ‘in a roundabout way’. The work is to be like a mosaic, composed of ‘fragments of thought’ indirectly related to the guiding theme. A modern reader might conclude that Benjamin was trying to torment the fixation on methodology exhibited by modern scholars. Actually, he was responding to different kinds of methodology of his own day, particularly positivism and traditional aesthetics.

According to Benjamin, science is an accumulation of knowledge-claims. Its purpose is therefore analysis, rather than representation (in the fully ‘mimetic’ sense). This accumulation of knowledge is useful, but Benjamin criticises those who see it as grasping the truth. The truth is an indivisible unity which cannot be grasped through the accumulation of knowledge. Rather, science itself requires philosophical inspiration to seem valid. It is a process of producing ‘concepts’, which group phenomena together.

Inductive theories are prone to being engulfed in scepticism, even when they recognise a need for systematisation. Deductive approaches are also criticised, because they assume a logical continuum among ideas. According to Benjamin, each idea is ‘original’ and ideas in general are a multiplicity. The experience of ‘truth’, in contrast to the accumulation of knowledge, is almost a mystical experience. It is something in which one is totally immersed, losing intention. It is reminiscent of Deleuze’s time-image and of mystical accounts of meditative, trance-like states.

The experience of truth occurs in a field made up of ideas. Ideas are not the same as concepts, which group phenomena. Benjamin also differentiates them from Platonic Forms as usually understood, which he considers deified concepts (in fact he also questions this standard reading of Plato). Rather, an idea carries the symbolic function into language. It is a bearer of the magical power which language inherits from superstition and sorcery. Following Leibniz, Benjamin argues that every idea contains an image of the whole world. Ideas have self-consciousness, distinct from outwardly-directed communication. One might think of Benjaminian ideas as expressive uses of language, creating zones of meaning rather than communicating. The intelligible world depends on the pure ideas, which are distant from one another and exist in a harmonious relationship. The perception of this relationship is what is termed ‘truth’.

Philosophy, in contrast to science, is all about representation. It is thus wrong to place it too close to science. The main purpose of philosophy is to restore the primacy of the symbolic aspect of language. Art, meanwhile, is about expression, rather than intuition.

Philosophy is to have its own postulates of method. It should seek interruption instead of deduction, tenacity instead of single gestures, repetition of themes instead of ‘shallow universalism’, and affirmative fullness instead of polemic. One effect of such postulates is the avoidance of technical terminology. The words over which philosophers argue are taken to be ideas in the full sense. The history of philosophy is a history of different configurations and juxtapositions of ideas.

Philosophy deals with the ‘realm of ideas’. Phenomena and objects enter into the realm of ideas only partially, through their essences. (A phenomenon, literally an observable occurrence, refers in philosophy to empirical things, objects, events, beings and so on). For Benjamin, this process is a kind of transubstantiation which redeems phenomena and objects. It rescues them from their construction as part of the existing system, and allows them to be reinscribed in new mosaics and combinations.

The purpose of this method is to aspire to an essence or truth which direct argument cannot reach. This philosophical task is incommensurable with the pursuit of knowledge. The truth is never identical to the object of knowledge. Truth is to be reflected upon, and has an inherent unity at the level of its essence.

Arguments for this separation of truth from knowledge include the distance between beauty and knowledge, with beauty often carrying an experience of truth, and the fact that past theorists whose knowledge-content has been surpassed – such as Aristotle continue to seem relevant at the level of truth. Such theories retain a feeling of relevance because of their systematic nature as an ‘order of ideas’. They are of interest as systems, rather than knowledge-claims.

Phenomena are redeemed through ideas. Ideas, for their part, need representing in the world of phenomena. The human mimetic faculty is the means to bring ideas into the world. Concepts simply group individual phenomena while leaving them as individuals. Redemption transforms individual phenomena into totalities, through conceiving their relations.

Phenomena are not incorporated in ideas. Rather, ideas are virtual. They are the objective, virtual arrangement of phenomena. At the same time, they belong to two different, incommensurable worlds. Ideas represent phenomena in terms of something radically other. ‘Ideas are to objects as constellations are to stars’. Phenomena limit how they can be represented by ideas. But ideas are necessary to symbolically construct relations among phenomena.

The main role of the idea is to represent the context in which phenomena – especially their extreme, and most telling, cases – coexist and interact. Ideas are obscure unless phenomena actually ‘gather round them’. Just as phenomena need salvation, so ideas need representation – their expression in phenomena.

Culture should be observed in its ‘origin’, its process of becoming. This process must be seen in the finished work, and seen as something incomplete. If a work or genre is original, it expresses a new determination of an idea (we might say, a new zone of becoming) which has not previously been expressed or which was revealed less completely before. Origins cannot be seen directly in works. They can be seen in the history and later development of a work or genre. Philosophy, furthermore, is the attempt to perceive ‘the becoming of phenomena in their being’.

It is through this idea of origin that Benjamin differentiates himself from the idealist attitude he attributes to Hegel: philosophers study essences, and if the facts don’t fit the essences, then so much the worse for the facts. For Benjamin, an idea is only interesting if it is ‘authentic’, and it is only authentic if it expresses a real process of becoming, at the level of observed phenomena.

Benjamin analyses the story of the Garden of Eden in terms of a fall from immediacy in language. In Eden, words directly express what they name. There is no need to struggle to communicate.

Philosophy is portrayed as a renewal or rediscovery of this primordial situation. Naming should not seek to conceptualise similarities. Rather, it should form connections between differences, between extremes.

Literary studies is criticised for classifying things into genres (concepts), without sufficient attention to ideas. Literary ideas become apparent only in extreme cases, at the limits to concepts. They cannot be found in deduction from the rules of genres. Effective contemplation instead focuses on the smallest details of a work.

The idea cannot be encountered through inductive observation of, for instance, the things tragedies have in common or the emotions they provoke. Inductive processes tend to remain within the field of habitual experience (Deleuze’s sensorimotor, Bourdieu’s habitus, psychology’s schemas). This experience always happens within one’s own historical period and worldview. Hence, there is a tendency to fail to see differences between, for example, the German baroque and ancient tragedies. They are treated as similar based on the similar reaction of a modern viewer, or even simply of an individual critic.

Benjamin is critical of the tendency to read back modern issues into older controversies. He argues that the ‘spirit of the present age’ is particularly prone to seize on past phenomena and ‘take possession’ of them without any feeling for their content, incorporating them into the self-absorbed fantasies of modernity. The historian is here seen as performing a substitution in relation to the creators of art – often disguised as empathy, or an emphasis on the author.

The special qualities of a genre, especially its historical forms, are obscured by conflation with more recent or more numerous examples. Benjamin here associates ‘form’ with the action or inner life of a text or genre. It is implicitly connected to its social context, the connections it retains with its social origins. Art in general, and drama in particular, can be understood only through its historical resonances.

In the case of German baroque or tragic drama (Trauerspiel), the topic of the book, Benjamin argues that it is misunderstood. It is either classified as tragedy, and fused with better-known classical works, leading to a misunderstanding of both, or classified as Renaissance theatre, and simply denounced for stylistic shortcomings. For Benjamin, these alleged shortcomings are actually characteristic features central to its analysis. Stylistic concerns prevented an ‘objective’ (historical or philosophical) understanding of German tragic drama.

While quite specific to this case, one could also imagine Benjamin’s critique being applied to conservative critics of cultural studies. Popular novels, film, television and so on have historical importance as organising logics within particular life-worlds. They construct systems of meaning and have considerable social importance. To dismiss their importance because of their failure to conform to canons of style, or to treat them as inferior instances of ‘high’ art, is to repeat the errors Benjamin criticises.

However, Benjamin also argues that some works of art are genuinely creative, and others not. He believes there are periods of ‘so-called decadence’, when original, non-imitative creativity seems out of reach. The period of German baroque literature is for Benjamin one such age. It was also an age ‘possessed of an unremitting artistic will’. This will was able to grasp the forms of artistic production, but not to produce outstanding individual works.

The period was also driven by a desire for a vigorous language matching the violence of historical events. The literature of the period thus captured aspects of its historical spirit. It was, like today, a period of global war and widespread questioning. It was an era when fixed certainties were collapsing and new theories coming into being, yet also in which this emergence was blocked. It was also arguably the period of the rising bourgeoisie, in which what are today mainstream ideas began to be articulated. Benjamin is thus excavating the origins of the contemporary world.

Benjamin’s concept of ‘essence’ is not the same as Derrida’s, nor is his concept of ‘representation’ akin to Deleuze’s. There are certainly cases where Benjamin would call ‘representation’ what Deleuze calls ‘non-representational’ or expressive, and where Benjamin would term a revelation of essence what Derrida terms a deconstruction of essentialism.

Science and analysis simply observe the present; they are of limited use in constructing a different future, as the contours of the future cannot be observed or tested. This is the basis for Benjamin’s separation of the ‘idea’ or ‘essence’ of objects from knowledge of them. The danger of analysis is that it reduces objects to their functions and hence can’t escape the present. ‘Essence’ here belongs to the future, like Marx’s species-being, and not to the present. ‘Essence’ here serves to release objects from their functional inscriptions, giving them something of a unique and recombinable value. The background implication here is the belief in a lost or future paradise, in which everything has its proper place.

It is not clear why Benjamin assumes the aspects of objects which are retained in their re-use, or reconfigured differently, are essences of the objects. Nor is it clear why classical philosophical concepts are particularly likely to serve as ‘ideas’ – as opposed to new concepts (as in Deleuze). In his reliance on essentialism, his theory arguably falls short of others which similarly emphasise the experience of the contingency of present arrangements.

However, Benjamin stands out for the aspiration or hope for a world where everything fits. This could be seen as a variant on the desire for abundance, or as a dangerous fantasy of imagined fullness. In practice, it is productive for Benjamin’s theory. Like the not-yet in Bloch, Benjamin’s aspiration for redemption fuels an experimental outlook and a dissatisfaction with social closure, the happy consciousness, and settling for the present. To accept a flawed world, and not aspire in a redemptive and revolutionary manner for its transformation, is to renounce the human capacity for mimesis and salvation, to settle for “hell”.

It is debated in the secondary literature whether Benjamin believes that a redeemed world is truly possible (as a post-revolutionary society), whether it is an absent horizon which must endlessly be pursued, or whether it is simply a change of perception, akin to a religious experience of Nirvana. His politics and many of his examples suggests it is possible: objects can in fact be rearranged, not only imagined differently. But does this leave him open to the objection that he must settle at some fixed order, which is then repressively imposed as ‘full’ and ‘complete’?

I would speculate that a ‘redeemed’ world is a world where the contingency and freedom of relations is permanently recognised and actualised in social, material and ecological relations – including relations to spaces, objects, images and time. Redemption happens, for instance, when factories are occupied and self-managed, or turned into squats; when roads are turned into gardens; when the wilderness overgrows the cities.

Redemption is disalienation – the recreation of direct relations. It is an expressive rather than instrumental world in which things relate directly, through their becomings, rather than indirectly, through their appearances. The ‘idea’, in such a world, is the intuition of the becomings of the other, as in the case of Athabascan hunters who can track animals by intuiting their likely movements.

Benjamin’s approach is also inflected by his critique of the order of ‘fate’. Things, and people, are sullied by being located within an order of things dominated by alienation. But things and people are open to a kind of profane illumination or redemption through their appreciation and reconfiguration outside dominant contours – out of sequence and out of tradition.

We see this kind of gesture recur across Benjamin’s work, as the function of allegory in literature, of flânerie, of collecting, of messianic time, of Surrealist art. The gesture in all its forms constitutes a glimpse of another world through the experience of something apart from its usual social connections, arranged in other combinations or without combination.

Benjamin’s philosophical method is designed to produce and prolong such glimpses. Yet the glimpses are not simply sublime moments of something unachievable. They involve an imperative force to overcome the order of things. Benjamin aspires to a change in perception such that the glimpses produce an entirely different world. The world is redeemed in revolution. This is most likely what Benjamin speaks of in terms of the ‘politicisation of art’. Art is politicised when it performs the function of producing glimpses of redemption.

[Part Two will be published next week. Click here for other essays in this series.]

7 Comments

Eugene Egan

Andy

Indeed 🙂

You’ll find a lot more on those parallels in Part 4 when it appears.

Walter Benjamin and Critical Theory | Philosophies | Scoop.it

[…] Walter Benjamin is one of the most influential critical theorists of the early twentieth century. His writings include original theories of the state, fascism and revolution. […]

The language of objects | Notes from the wreck

[…] Phenomena are redeemed through ideas. Ideas, for their part, need representing in the world of pheno… […]

Nizar

L

Mukesh Yadav

Great insight into thoughts of wizards.

The study for a redemptive world is to be welcomed especially in light of globalisation, austerity and ever decreasing natural resources.