The Colonisation of Brazil Ghosts of History

Ghosts of History, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, July 10, 2015 19:18 - 6 Comments

By Xain Storey

South America is arguably one of the last regions to have been touched by prehistoric humans. The Aboriginals there today descend from people who had lived there from up to 15,000 years ago. From archaeological findings, Neolithic cultures had inhabited the rainforest from 11,000 years ago.

The colonial history of Brazil is, like that of North America in general, bound up with the Transatlantic Slave Trade. It is imperative to understand that the victims of colonialism also include Africans, who were forcibly removed from their homelands in order to build on others’ around the globe. Today, there are over 900,000 indigenous Brazilians, and around 14 million Black/Afro-Brazilian, with around 83 million identifying as ‘pardo’ (Brown or mixed race), and 91 million Whites.

In 1494, following the return of Christopher Columbus and the publicisation of his voyages and ‘discovery’, the Portuguese signed the Treaty of Tordesillas with the Crown of Castile (which, today, comprises part of Spain). This was essentially an imaginary line that the Portuguese and Castilians drew to divide up the known land outside of Europe. Whilst the majority of the West (Americas) were claimed as Spanish territory, Portugal laid claim to some parts of it, including Newfoundland and Labrador (believing it their right due to Caboto’s ‘discovery’), as well as Brazil, originally, and mistakenly, called Ilha de Vera Cruz, meaning ‘Island of the True Cross’, later changed to ‘Land of the Holy Cross’, after explorers realised it was part of the South American continent.

In the year 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral and his crew, who were tasked with travelling to India by King Manuel I of Portugal, stopped over on the coast of Brazil. At this time, the indigenous population was approximately 8-11 million. Within a century, 90% of them would perish, as a result of foreign disease and murder.

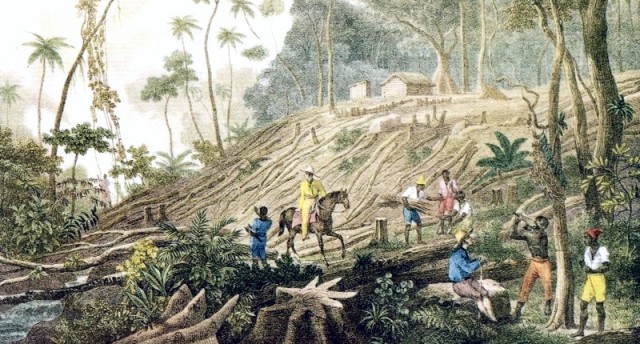

Between 1500 and 1530, Europeans established trading posts with the (eventually enslaved) indigenous peoples, who helped the Portuguese harvest brazilwood (or Pau-Brasil, after which Brazil itself was named) and brought it back to Portugal in order to sell the extracted red dye. The first Portuguese settlers arrived in Brazil in 1531 and, due to Dutch and French hostilities along the coastline, aimed to establish a permanent colony, commissioned by the Portuguese Crown. The first such colony, São Vicente, was founded by Martim Afonso de Sousa in 1532.

Up until 1536, 15 captaincy colonies were created by the Portuguese Empire, with the goal of resource exploitation and further expansion into indigenous territory. Each captain-major (formerly a Portuguese nobleman) governed an autonomous, private administrative unit that imported feudal economics from Europe. It was during this time that Natives were forcibly taken, through deceit and violence, to work as slaves to grow and harvest sugarcane on sites called ‘engenhos’, which had little difference to plantations.

Despite the relative success of the Pernambuco captaincy, others were unable to gain enough capital. As such, in order to re-establish a healthy surplus for the Portuguese Empire, the Crown formed the Governorate of Brazil in 1549, which united Brazil into a single colony, but the administrative units would remain as privately owned districts, answerable only to the governor-general of Brazil. Until 1775, colonial Brazil would undergo various geopolitical changes, either due to the economic whims of the Crown or disputes over territories with other European invaders, such as the Dutch in the mid-1600s.

From the 1620s onwards, invaders, who were settled in São Vicente (later São Paulo), organised private expeditions, called bandeirantes, which focused on killing or enslaving indigenous people, often to use them to find other Natives. They were able to do this by disguising themselves as Jesuits, whom the Natives welcomed into their ever-decreasing territory despite being fully aware their motive was to convert them to Christianity. The bandeiras would murder or capture the Natives, and those who escaped faced dying from infection with foreign diseases. This, in conjunction with the more nationwide dispossession of their lands and heritage, resulted in the Natives fleeing into more secure, arboreal regions. Despite this, Europeans would still search for Aboriginals, and attempt to kill them and take their land, sometimes knowingly using their vulnerability to foreign diseases as a weapon.

Though the importation of African slaves occurred from the mid-1500s, the continuing expansion of Portuguese settlements, the rapidly decreasing Native population (due to disease, murder, and forced migration) for slave labour, and a growing demand in the sugar trade in the 17th century, resulted in the intensification of Portuguese export of slaves to Brazil. It was from here, until the mid-to-late 19th century, that between 4 and 5 million Africans (40% of the total number of slaves exported during the Transatlantic Slave Trade) were taken to Brazil, mainly from West-Central African regions, as well as Mozambique.

During this period, the famous martial-art Capoeira was also being imported into Brazil. Few records are available, but oral evidence suggests that it was originally a Central African practice, subject to much variation and refinement when brought to Brazil. On plantations, slaves would practice Capoeira (with their feet usually in chains) as a mixture of dance and fighting, sometimes disguising the latter if slave owners punished those who practised it. Between 1808 and 1889, the Portuguese Empire, and later monarchy, attempted to eradicate capoeira by prohibiting it, as they viewed it to be ‘savage’, representative of the lower-class, African side of Brazil, which did not conform to the ideology of white supremacy, and indeed threatened it, due to its history of usage in slave resistance. Those who were caught practising it would be imprisoned, mutilated, and tortured (subjected to amputations and lashings, for example). Capoeira survived nonetheless, and would become a world famous martial art.

Africans who escaped the barbaric sugar plantations and diamond/gold mines would form Maroon communities, called quilombos, where they would build societies free from slavery, aimed towards resistance against the settler colonialism of Portugal. Many of the runaway slaves used capoeira as a defence when Europeans would attempt to recapture them. Quilombolas also welcomed escaping Natives, mixed Brazilians (of European and African/Indigenous descent), and impoverished whites. The largest, and most famous quilombo was called Quilombo dos Palmares, which served as a major force of resistance for over 70 years. In 1694, however, after multiple victories against Portuguese invaders, the once 30,000 strong quilombo was destroyed, and its peoples displaced, moving into smaller communities that exist to this day under adverse conditions, as a movement for reparations and general well-being.

Aside from Quilombos, Afro-Brazilians organised mass revolts against Portuguese slavers and planters, most notably the Malê Revolt of 1835, which took inspiration from the successful Haitian Revolution. Though the Muslim Uprising was unsuccessful, and was met with executions, murder and forced conversions, it arguably facilitated the abolition of the slave trade in 1851, by making the invaders fearful of future revolts. The settler state looked for other financially viable methods of extracting capital, such as wage labour. Amidst this, indigenous people’s lands were being destroyed through deforestation and constant expansion for rubber, coffee beans, and precious stones.

Slavery itself was not abolished in Brazil until 1888 and, even then, mass prison systems and vagrancy laws were developed in order to criminalise and incarcerate non-whites (who formed the majority of impoverished persons in the post-slavery era), using them as slave labour exempt from legal scrutiny. Plantations were transformed into penal colonies in the early 1900s, giving planters rights of private police forces to hold people whose manumission certificates contained clauses that allowed for their re-enslavement if they were deemed to be criminals – a physiological disposition in dark-skinned people, according to the constructions of European science. Ordinary jobs were given primarily to Europeans, and former slavers and planters were compensated for abolition in the millions, something that occurred throughout the world for European states complicit in slavery.

In the mid-20th century, the indigenous people of Brazil were subjected to further genocide by the government, some of which was documented in the 7,000-page-long Figueiredo Report of 1967, which was not released until 2013 (it has yet to be released to the public). Over 134 officials were involved in over 1,000 crimes, including mass shootings, poisonings, rape, enslavement, displacement, bacteriological warfare, forced acculturation, and torture, all which fall under the crime of genocide. The 1963 ‘massacre of the 11th parallel’ is detailed also, in which prospectors threw dynamite from a small plane onto a village of Cinta Larga people, killing 30 of 32. To this day, no one has been prosecuted (due to retroactive principles), and no one has been remunerated in any form. Furthermore, today’s problem of large-scale deforestation occurs at the cost of indigenous lives and culture. International corporations and local settlers are heavily invested in the destruction of Brazilian rainforest, despite the consequences for the people living there (who have been preserving and protecting the environment for centuries), and for the world in general. Genocide is ongoing.

Today, the myth of racial harmony persists, with inequalities in Brazil deemed worthy only of a perfunctory glance. Quilombos continue to face adverse conditions, and Black Brazilians remain disproportionately deprived, with poor housing in favelas, little access to good education, poor access to healthcare, and being inordinately brutalised, with impunity, by a police force that is reportedly one of the ‘deadliest in the world’. Moreover, Black people continue to be demonised for a ‘culture of violence’, despite their socio-economic conditions being violently imposed.

In many ways, little has changed in terms of the murder and deracination of indigenous Brazilians. Nor has much changed in terms of the anti-Black, racist institutions that dehumanise, impoverish, imprison and murder Black Brazilians. Settler colonial Brazil prides itself on being a ‘racial democracy’, a tag that appears to be nothing more than a cover, masking a reality of white supremacy that is deeply and historically embedded into the fabric of the nation.

For mnore essays in this series, visit the Ghosts of History page.

6 Comments

Brian

Thank you so much for this highly informative and well-written article.

Great read!

Eman C.

Informative, and well-written. Need more access to information like this to help put an end to White supremacy and collectively decolonize. Thank you!

Keira

Excellent piece of work. One of the best summaries of colonization in Brazil. I’ve read all your pieces and your work just keeps getting better. Thank you. Definitely sharing this with everyone.

Xain explores the continuing pillaging of entire continents by the living history of Western colonialism. This history produced its own internal colonialism where the sons and daughters of newly independent countries became agents of their former European imperial masters. Xain’s informative piece reminds us that the land nor the people have forgotten when they died in masses in mines or on plantations. They have not forgotten Africa becoming as Karl Marx’s wrote “a warren for the commercial hunting of black skins”. They can not forget because the conditions of their lives reminds them everyday. It’s been over 500 hundred years since Christopher Columbus brought the plague of European guns & germs upon the old world and the new, yet our memories or short and incomplete. We are taught that history is something that happened, long ago, but the past is an illusion. The past and the present is one continuous event, there is no real specific point in which Rome rose and fell. We carry history with us, it is handed down to us like DNA from our parents. Pieces like these shock us into considering how little we’ve changed and how far we still have to go.

johnberk

When I’m drinking my morning coffee which comes from Brazilian plantations, I always think about the conditions workers have to endure. Has it changed? And how much? What about the inequality. This article is just another piece of evidence that Brasil still has many issues unresolved.

This is a brilliant overview, and an issue rarely discussed. One of CF’s best columns