Arts & Culture: Redo Pakistan

Arts & Culture, Features - Posted on Saturday, August 21, 2010 12:09 - 1 Comment

By Hamja Ahsan and Fatima Hussain

With Pakistan now a major item on the news agenda – instability, violence, and recently, of course, the devastating floods – what hope is there for Pakistani artists? Can they hope to address the situation of the country in a way that could possibly make a difference? Is the contemporary art world just too Eurocentric to let them in?

This week, Ceasefire deputy editor Musab Younis caught up with Fatima Hussain and Hamja Ahsan, the curators of an innovative new transnational art project: ‘Redo Pakistan’. Its second issue is launching at the Aicon Gallery in London on Tuesday, 24 August 2010, kicking off a series of events in London and the Midlands. The launch will include fundraising for the victims of the recent floods in Pakistan. You can also donate to the DEC, which is coordinating Britain’s relief effort, here.

1. What is REDO PAK?

FH: Redo Pakistan is a nomadic art project that delves into the contested histories and futures of South Asia. It was initiated early last year, when a call was sent out asking: “What if Pakistan were to be restored and stabilized geographically, politically and intellectually? What would a Pakistan, reconstructed now, look like?”

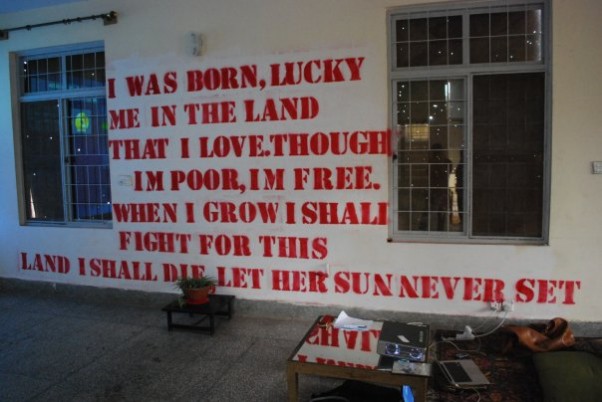

The exhibit started life at the Shanakht festival in Karachi (Pakistan’s largest contemporary arts festival) the first time round. It was ransacked by Pakistan People Party activists due to a disagreement over a photograph displayed at the festival depicting Benazir Bhutto sitting on the lap of general Zia. The next stop Redo Pakistan made was in Lahore. This time, the works had all been translated into a newspaper to be handed out to the audience in a gallery space. We choose a form that was transient, urgent, and publicly inviting.

Redo Pakistan is now a yearly publication that activates further chain of events. This time the call sent out was “Declaration of WAR against the Present Time” (the subtitle of the poetry compilation, Zarb-e-Kaleem by [Muhammad] Allama Iqbal). We are interested in the very contemporary formations of curatorial practice. This declaration is being done through publications, newspapers, talks, performances and film screenings: it is like a production chain.

At our last stop earlier this year, the project was curated at The Guild Gallery, New York in a show called Structures Within an Intervention. We had planned a launch in Pakistan on the August 14. The events have been delayed because of the recent floods.

Redo Pakistan has a launch planned for London between 24 August and 12 September.

2. Is the contemporary art world Eurocentric?

HA: I bought Fatima Making Myself Visible by Rasheed Araeen as a present from London to Pakistan, and I think a lot of the observations and grievances from the Black Arts movement 25 years ago are still pertinent. Many of the observations Eddie Chambers made about the politics of exclusion you can still see at an institution like the South London gallery (despite the multi-million pound makeover) where – despite being in an majority Afro-Caribbean settlement area – the only regular black person one sees is the aging security guard.

Then there is what I call the Vyner Street Fashionist problem: the ultra-cliqueness of advanced, indie-club, indentikit, hipster, skinny jeans communities. That makes me sick. Sure, there has been the huge regional survey shows like Indian Superhighway and an economic boom of the dominant Asian economies. But one sees new hierarchies of exclusion. Is power really being redistributed? Who is the head and who is the body?

Eminent international curators like Okwui Enwezor do not change the situation of a wall of exclusion in local settings and exchanges in majority Black and Asian diaspora settlement areas such as in Peckham, Tower Hamlets, Deptford etc. I also think the fact that RAQ’s media collective has done 1,000 public commissions in the last year is no good thing – it shows the laziness and complacency of white institutional power.

The theoretical parameters of art practice are very much Eurocentric and art world bookshops like Koening are very much structurally racist. You see huge coffee table books on Oriental carpets and African masks downstairs in the basement, and upstairs all the Deleuze-o-babble and Zizek’s provincial material Marxist bitch-fighting. Even postcolonial studies, as it was institutionalized in Britain through Robert J. C. Young, is too much a detour of French Theory.

That’s why we invoke Muhammad Iqbal against this grain. His central important to twentieth century history I still feel isn’t recognized in the West (for example with regard to the Iranian Islamic republic, which calls itself the republic of Iqbal, the formation of modern South Asia, and so on.) These are the wider structural problems of the knowledge-power nexus.

3. REDO PAK is explicitly political, but can art from Pakistan ever avoid politics? Should it try?

HA: Before we get into politics with a big P, there are all sorts of institutional obstacles one has to deal with. The Bhavan centre, for example, invited us, let us go ahead with an Arts Council application, and gave us a contract and dates knowing Fatima was flying from another country. Then they ejected us with little explanation other than that we are “political”.

Another institution would not let us have Islamic Relief do a collection for the Pakistani floods, which was nonsensical considering the institution endorsed the Disasters and Emergency Committee, which is a coalition of several charities including Islamic Relief.

I think the activist community has a very instrumental and didactic understanding of art practice. One hears the same lame lecture on Banksy at Marxism and the same hasty local-library trashpit of an exhibition.

Redo Pakistan operates in some realm between fiction, imagination, and document, not related to any particular present as such. It expands a possibility and an opening, or at least aspires too.

FH: Well, ‘politics’ is a funny word. The word ‘polis’ means ‘city’. Politics could be a way of dealing with the city through language, culture, dialogues, etc. We feel art can never avoid politics just as it can never avoid the city.

Redo Pakistan however, is not dealing with ‘political issues’ as such. It comes from the need to address the problems within the art of the region, including culture, language, built architecture, history, and colonialism and its influences.

Art from Pakistan has never been able to avoid these questions. Now that Pakistan is the recent focus in the world media due to natural disasters, unstable governance and strained borders, it has become even more difficult for the artist to avoid politics of any kind. These are the questions the artist faces every day.

4. What’s your opinion of the state of the contemporary arts in Pakistan?

HA: There seems to be forms of embassy representation too. It is often instrumentalised as a form of diplomacy: Salima Hashmi doing her show Hanging Fire for the Asia Society, for example.

FH: Contemporary art in Pakistan is very blatantly dealing with the politics and with the current scenario of the country. There seems to be some sort of urgent necessity that is driving the arts today. Artists are taking a lot from their ‘city’ to deal with the “image of Pakistan” in the broader world. For us, what is lacking is the immediacy of this art where it chooses the audience.

The art (mostly) has failed to connect with the real. It seems to be still floating within the art institutions, the elite, and the whitewashed gallery spaces. It somehow fails to take up the social responsibility it has towards the art itself, the audience and the politics.

Hamja Ahsan and Fatima Hussain have been working together on transnational arts projects since October 2008 as Other Asias.

www.otherasias.com

1 Comment

THE ARTISTS FIGHTING TO ‘REDO PAKISTAN’ « FREE ART LONDON LIST

[…] Interesting interview on this project at Ceasefire mag here: https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/2010/08/arts-culture-redo-pakistan/ […]